US business activity growth remained close to stalled for a second month in a row in September, according to flash PMI data compiled by S&P Global, suggesting that the pace of economic growth has weakened in the third quarter.

Companies reported that demand remains under pressure from the increased cost of living and higher interest rates, which have dampened service sector growth in particular, after robust growth seen earlier in the summer. Manufacturing, meanwhile, remains in the doldrums.

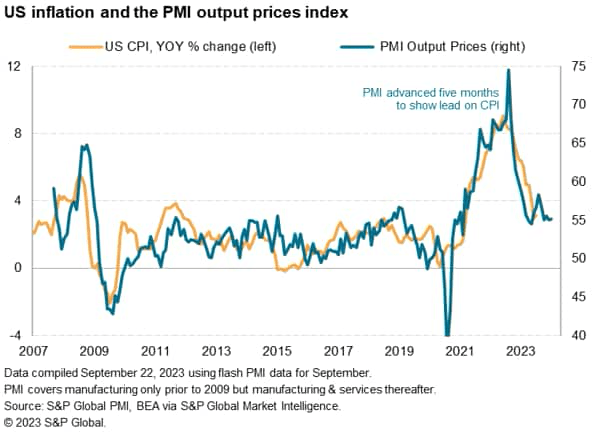

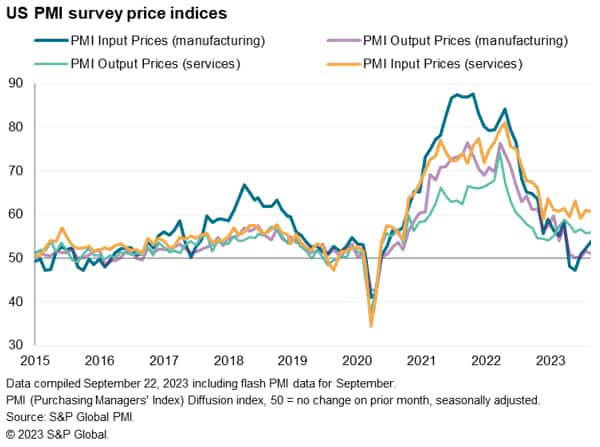

The survey price data meanwhile indicate stubborn stickiness of inflation, consistent with CPI running around the 3% level in the months ahead, with higher oil prices presenting some upside risks to inflation.

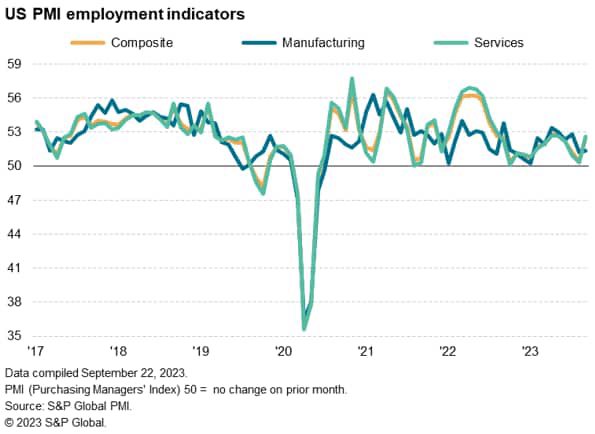

Wage growth also remains a widespread driver of inflation, and employment growth ticked higher in September to add to signs of labor market strength.

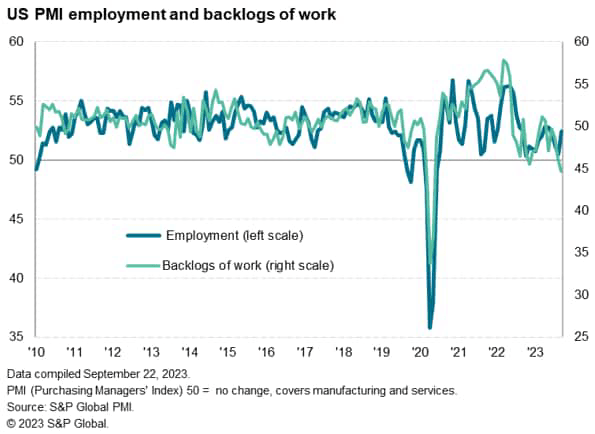

However, with backlogs of work falling at a marked rate, and future output expectations slipping lower, there are question marks as to how long companies will continue to boost payroll numbers at the current rate.

Slower growth

US business activity remained largely stalled for a second month running in September. At 50.1, nudging down from 50.2 in August, the headline S&P Global Flash US PMI Composite Output Index signaled the weakest upturn in activity since February and only a fractional expansion.

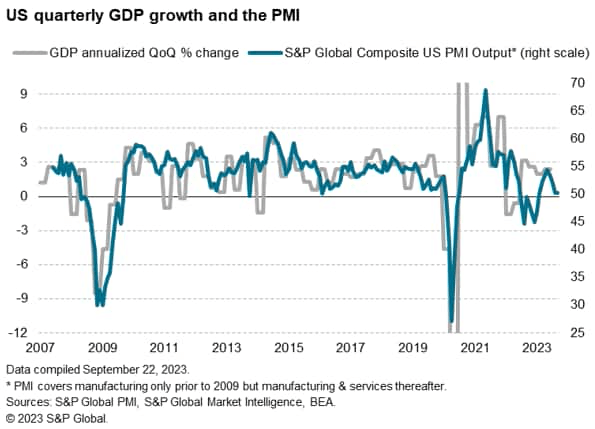

The low PMI readings in August and September point to a more subdued picture of the US economy in recent months than the robust expansion seen in the second quarter.

Whereas the headline PMI averaged 53.6 over the second quarter, the third quarter average has fallen to 50.8. This points to a moderation of annualized GDP growth from approximately 2% to 1% between the second and third quarters. The latest available GDP estimate puts second quarter growth at 2.4%.

There has been some confusion recently regarding the GDP data from the US, notably due to a historically wide spread developing between the GDP and GDI measures.

In theory, these two metrics should follow identical paths, with the former measuring output and the latter measuring the income derived from that output.

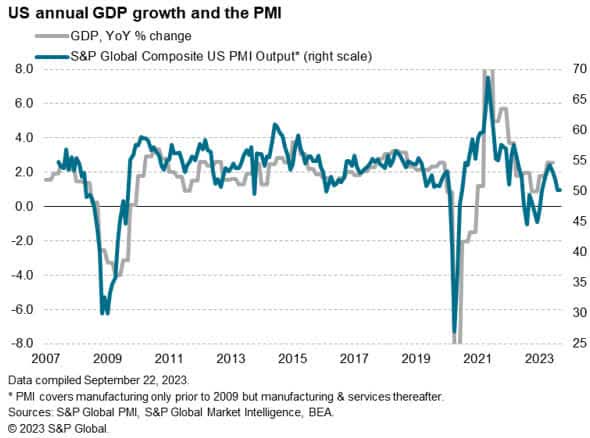

However, while gross domestic product has seen continuous robust growth over the second half of 2022 and the first half of 2023, gross domestic income has plotted a different, more worrying, path which is much more in line with the PMI.

Both GDI and the PMI in fact signaled economic contractions in the fourth quarter of 2022 and the first quarter of 2023, followed by a return to growth in the second quarter. The comparison of the PMI with GDI therefore suggests that GDI could weaken again in the third quarter.

Interestingly, the PMI data also align closely with the annual (year-on-year) change in GDP, and therefore likewise point to the annual rate of economic growth cooling in the third quarter.

Factory malaise persists

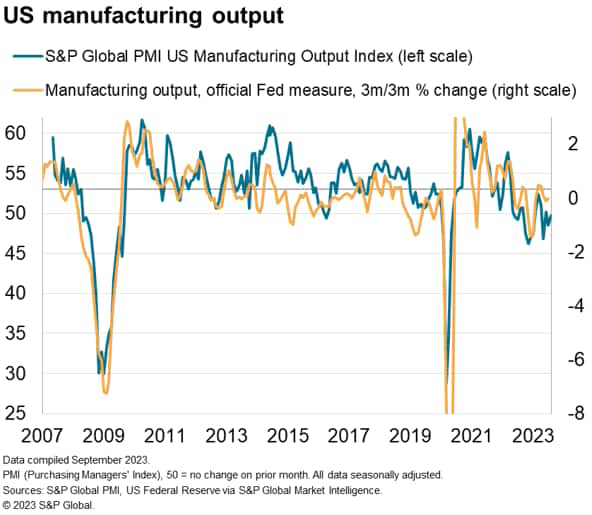

Looking at sector trends, manufacturing output fell marginally in September, down for the third time in the past four months, suggesting that the brief return to growth at US factories seen earlier in the year – sparked in part by China’s reopening from COVID-19 – has continued to falter, albeit only modestly for now.

However, further production losses may follow. While production has been supported by factories fulfilling orders placed during the pandemic, assisted by supply chain improvements, these accumulated backlogs of work have now fallen continually over the past year, due in part to an absence of new order inflows.

New orders for goods fell for a fifth successive month, leading to another marked fall in backlogs in September, although the rate of decline moderated to the lowest over this period. This continued depletion of order books bodes ill for the production trend in the months ahead.

Service sector acts as increased drag on economy

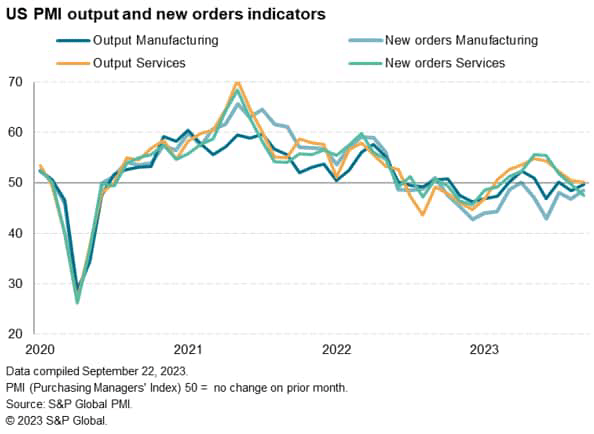

The business situation has meanwhile been changing even more notably in the service sector. After hitting a 13-month high in March, the rate of growth of business activity in the service sector has since waned to signal only very modest gains in both August and September, with the latest reading the weakest since the sector’s recent revival began back in February.

Having reported a surge in demand for many service-oriented activities such as travel, tourism and recreation earlier in the year, this boost is now moving into reverse.

There are signs from survey responses that the tailwind from the reopening of the global economy from COVID-19 is being increasingly offset by downward pressure on spending from the increased cost of living and higher interest rates.

New business inflows into the service sector consequently fell for a second successive month in September, with the rate of decline accelerating. Moreover, the decline in service sector new business exceeded the rate of loss of orders in manufacturing for the first time in a year, meaning the services economy is now leading the demand drag on the economy.

Sticky CPI

The survey’s selling price data meanwhile continued to point to consumer price inflation sticking around the 3% mark. The index of average prices charged for goods and services was unchanged at 55.1, down from 58.3 back in April but still elevated by historical standards.

Although manufacturers’ selling prices barely rose again in September, thereby continuing to act as a major dampener on the overall inflation trend, prices charged for services rose sharply again (the rate of increase even nudging higher) amid elevated cost growth, the latter linked to wages and higher energy costs.

Worryingly, higher wage and oil prices were also widely associated with a steepening rate of input cost inflation in manufacturing, albeit from a low base.

Employment rises, for now

Finally, looking at the labor market aspect of the flash PMI, September saw employment rise at a rate that, by a narrow margin, was the fastest for four months. The upturn in hiring was led by the service sector, though factories also continued to take on more staff at a modest pace.

There are suggestions, however, that the jobs trend could weaken again. Backlogs of work – a key proxy for capacity utilization – fell in September at a rate which, barring early pandemic lockdown months, was the steepest since comparable data across manufacturing and services were first available in late 2009. Backlogs fell in both sectors, with the service sector seeing a notable acceleration in the rate of decline.

The disappointing order book trend played a key role in subduing companies’ expectations about growth in the year ahead. Future output expectations fell to a nine-month low, led by a souring of optimism in the services economy.

Falling jobs would mark a key weakening in the economic picture, but the associated drop in wage bargaining power would also bring welcome news on the fight against inflation. We therefore watch how these metrics develop in the coming months with close interest.

Original Post

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.

Read the full article here

Leave a Reply