This piece revisits the current U.S. fiscal debt and deficit system, in light of the ongoing problems in the U.S. bond market, and explores some investment themes amid this very “macro heavy” environment.

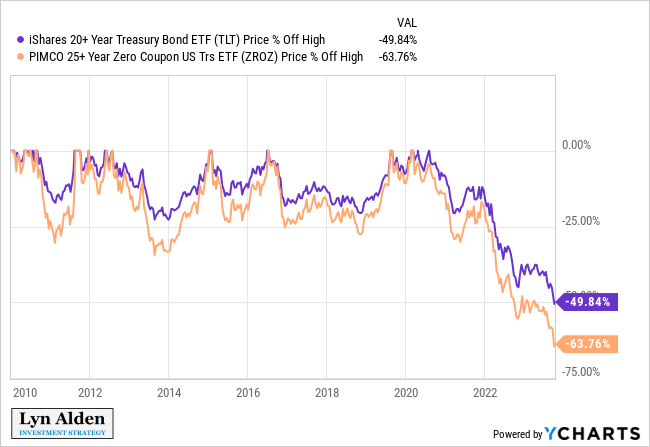

Long duration bonds have endured their worst drawdown in history:

YCharts

I’ve been bearish on bonds for a number of years now (see “The Bond Market is Spookier Than the Stock Market” from July 2019, “Yes, Treasuries Do Have Risk” from April 2020, and “Treasury Market Dissonance” from August 2020), but the nominal degree of this drawdown over the subsequent 3-4 years has been surprising even to me.

I think the main part of this drawdown is mostly done for the time being, and TIPS are looking interesting here with their positive real yields, but the overall fiscal picture remains highly problematic.

An Unstable System

In various fields of engineering, such as control engineering or mechanical structural design, the concept of stability is very important, and it means something quite specific.

RoyMech

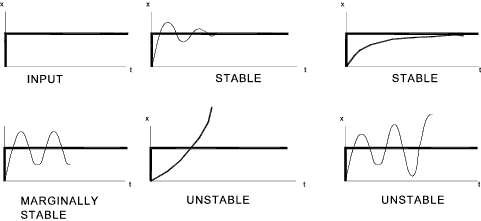

A system is either stable, unstable, or marginal, as shown by the pictures above.

-A stable system has a bounded output that reduces over time when given a bounded input. It tends towards calmness. If you hit a metal beam with a force, for example, the resulting vibrations in the beam will diminish in intensity over time. If you have an electromagnet and sensor system trying to levitate a metal ball by measuring the position of the ball and automatically varying the power of the magnet accordingly, a stable system will be able to reduce the ball’s oscillations until it hovers motionless. If you poke the ball with a small force, it will oscillate a bit from the dislocation, and then return to calmness.

-A marginal system has a bounded output that remains in motion when given a bounded input. In other words, the system might keep oscillating but the oscillations won’t get worse. It would be like if you poke a levitating metal ball and it just keeps oscillating but still able to levitate there. The control system is keeping it in check but is unable to get it back to calmness. Every time it applies a magnetic force it slightly overshoots, and then when it pulls back on the magnetic force it slightly undershoots, and so the ball keeps getting pushed around, but not getting worse.

-An unstable system has an unbounded output when given a bounded input. The oscillations will keep getting bigger, like how if you push a child on a swing at the perfect time while she is already starting to travel in the direction of the prior push, then you can apply a pattern of pushes that keeps her going higher and higher each time even though your push strength doesn’t change. The inputs are cumulative into a larger and larger output oscillation. This is how a singer can shatter a wine glass with her voice if applied to the glass’s mechanical resonance frequency, or how soldiers marching over a bridge can collapse the bridge if their unified footsteps match the bridge’s mechanical resonance frequency.

When thinking about the financial system of a developed country like the United States, our mental model generally views them as marginal systems: a series of oscillations that stay within the same overall bounds. Sometimes debt levels go up, and sometimes we need to tighten our belts so that debt levels go down. Sometimes the central bank tightens monetary policy, and sometimes it loosens it. The financial system, in other words, is thought of as being similar to how it was 20 or 40 years ago.

But in reality, most financial systems are unstable. They have an unbounded output in the sense that sovereign debt as a % of GDP keeps growing over time. Fortunately, the frequency of these systems is very long, so it takes decades for problematic levels of instability to build up to the point where the output gets out of control.

When it does get out of control, the system needs to be reset, recapitalized, or restructured in some way. In other words, sovereign bondholders lose purchasing power through nominal default or, more commonly, through inflation. To use the control system analogy, the oscillations get out of control, the electromagnet drops the ball, and it has to be picked back up and put back in with some fixes.

Three Eras of Financial Instability

We can divide the modern (post-telegraph) era into three main global financial orders.

International Gold Standard (1871 to 1914)

Prior to the invention of the telegraph, there was very limited ability (e.g. fire signals in the night) to send information faster than the speed of human travel. The telegraph was invented in the 1830s, but it wasn’t until the 1860s that it was deployed across the American continent, across multiple European countries, and across the Atlantic Ocean to link the whole Western world together. Separately, the Franco-Prussian war ended in 1871, bringing a period of peace to Europe.

The combination of fast long-distance communication and complex paper financial instruments greatly increased the speed of commerce globally, at a time when gold was used as money. As a result, gold had to be increasingly abstracted in order to keep up. And this abstraction was done with credit.

The international gold standard is generally considered by economists like Barry Eichengreen to have operated from 1871 until the outbreak of World War I in 1914. Under this scheme, gold was the base layer of money, and countries pegged their currencies to gold at a fixed rate. Whenever too much gold left a country or left central bank coffers, then that country could raise interest rates to attract more gold back into the country. There was a certain balance to it; a perception of stability.

However, it was unstable underneath the surface. It was almost too efficient for its own good; physical gold rarely had to change hands. Hardly anyone wanted to withdraw and hold gold, and so an increasing number of paper claims existed for gold relative to the actual amount of gold. Most things were an abstraction built on an abstraction, with a lot of leverage. In his 1875 book Money and the Mechanism of Exchange, William Stanley Jevons described the efficiency of the system:

England buys every year from America a great quantity of cotton, corn, pork, and many other articles. America at the same time buys from England iron, linen, silk, and other manufactured goods. It would be obviously absurd that a double current of specie [gold coins] should be passing across the Atlantic Ocean in payment for these goods, when the intervention of a few paper acknowledgments of debt will enable the goods passing in one direction to pay for those going in the opposite direction. The American merchant who has shipped cotton to England can draw a bill upon the consignee to an amount not exceeding the value of the cotton. Selling this bill in New York to a party who has imported iron from England to an equivalent amount, it will be transmitted by post to the English creditor, presented for acceptance to the English debtor, and one payment of cash on maturity will close the whole circle of transactions. Money intervenes twice over, indeed, once when the bill is sold in New York, once when it is finally cancelled in England; but it is evident that payment between two parties in one town is substituted for payment across the whole breadth of the Atlantic. Moreover, the payments may be effected by the use of cheques, or the bills when due may themselves be presented through the Clearing House, and balanced off against other bills and cheques. Thus the use of metallic money seems to be rendered almost superfluous, and, so long as there is no great disturbance in the balance of exports and imports, foreign trade is restored to a system of perfected barter.

However, he also posed a warning. This system was so efficient (he used the term “excessive economy” to refer to high levels of efficiency), and the system was levered 20-to-1:

It is requisite, too, that our bankers, financiers, and merchants should regulate their operations with a thorough comprehension of the immense system in which they play a part, and the risks of derangement and failure which they encounter by over-severe competition. No one doubts that alarming symptoms have during recent years presented themselves in the London money market. There is a tendency to frequent severe scarcities of loanable capital, causing sudden variations of the rate of interest almost unknown thirty years ago. I will therefore in the next chapter offer a few remarks intended to show that this is an evil naturally resulting from the excessive economy of the precious metals, which the increasing perfection of our banking system allows to be practised, but which may be carried too far and lead to extreme disaster.

[…]

Mr. R. H. Inglis Palgrave, in his important “Notes on Banking,” published both in the Statistical Journal, for March, 1873 (Vol. xxxvi. p. 106), and as a separate book, has given the results of an inquiry into this subject, and states the amount of coin and Bank of England notes, held by the bankers of the United Kingdom, as not exceeding four or five per cent. of their liabilities, or from one twenty-fifth to one twentieth part. Mr. T. B. Moxon, of Stockport and Manchester, has subsequently made an elaborate inquiry into the same point, and finds that the cash reserve does not exceed about seven per cent. of the deposits and notes payable on demand. He remarks that even of this reserve a large proportion is absolutely indispensable for the daily transactions of the bankers’ business, and could not be parted with. Thus the whole fabric of our vast commerce is found to depend upon the improbability that the merchants and other customers of the banks will ever want, simultaneously and suddenly, so much as one-twentieth part of the gold money which they have a right to receive on demand at any moment during banking hours.

Indeed as the era of peace in Europe ended with the outbreak of World War I, this highly leveraged system failed. Gold pegs were subsequently paused and broken throughout the interwar era. Vast sums of money were printed relative to the amount of gold in the system, and anyone holding paper claims for gold was defaulted on and sharply devalued. It was like punching someone who was in the process of trying to juggle way more balls than they have hands.

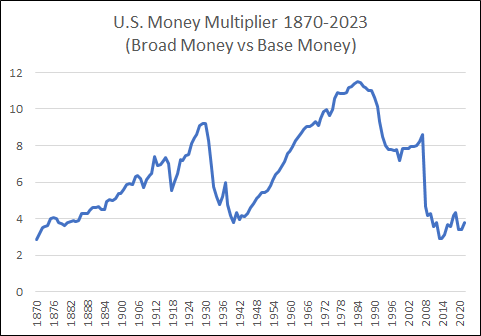

One way to visualize this is by looking at the money multiplier and total level of credit in the United States, which was better positioned than Europe throughout the war years.

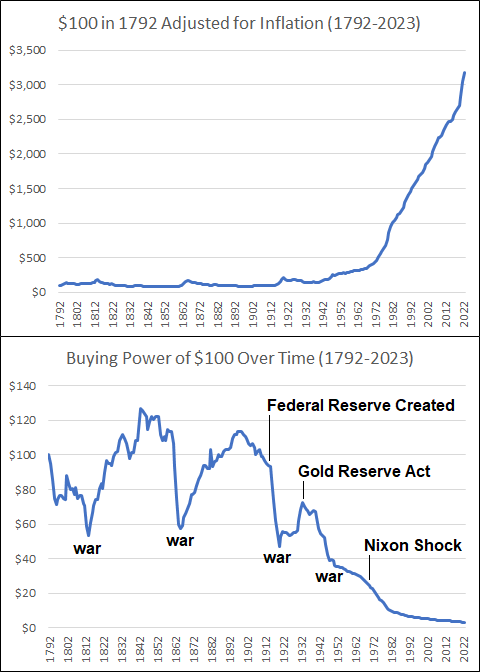

The ratio of broad money to base money in the U.S. increased from around 3x in 1870 to 9x in 1929, just prior to the banking collapse and Great Depression. And even base money itself was only partially backed by gold:

Lyn Alden, via data from macrohistory.net

With a double-digit ratio of the amount of broad money in the system (all of which is redeemable for gold on demand) relative to the amount of gold in the system, it was inherently unstable and prone to failure. Gold pegs were broken, and the currency was sharply devalued in order to bail out the highly leveraged system.

They ended up breaking the gold peg, dramatically increasing the base money supply, and recapitalizing the banking system.

Lyn Alden, via data from the US Treasury and Federal Reserve

Bretton Woods System (1946 to 1971)

As World War II came to a close, allied forces met in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire in 1944 to discuss the next monetary system, and it was partially implemented in 1946. Under this scheme, the dollar would be backed by gold, but redeemable only to foreign central banks (it was actually illegal for Americans to own gold from the mid-1930s to the mid-1970s). Central banks could hold dollars and dollar-denominated assets like Treasuries and could peg their currencies to the dollar.

In 1958, they eliminated international exchange controls, which had been in place during the post-war era. They sought to open financial borders and let market forces go back to work as global trade normalized. This marked the true beginning of the full Bretton Woods implementation. However, the system was unstable; the financial system was fractionally reserved, and yet there was only a finite amount of gold in the U.S. Treasury’s reserves.

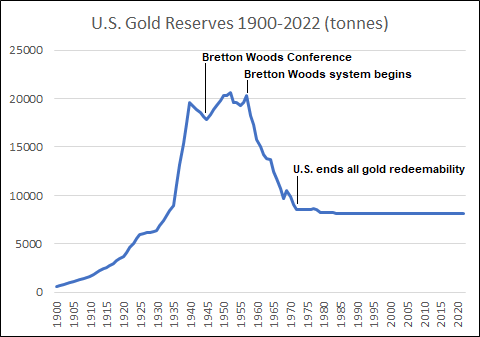

From 1950 to 1970, the amount of base dollars in the United States more than doubled, and the amount of broad dollars more than tripled. Offshore dollars kept increasing in supply as well. As soon as exchange controls were eliminated, the foreign sector began rapidly redeeming ever-increasing dollars for ever-decreasing U.S. gold reserves. Reserves fell from 20,000 tons to 9,000 tons very quickly. That was the instability of the system; the U.S. gold reserves constantly fell during its implementation which rendered the ever-growing currency supply less and less backed by gold:

Lyn Alden, via data from the World Gold Council

In 1971, President Nixon defaulted on the promise of gold redemption and ushered in the era of fiat currency. Many people blame him for that particular moment, but the uncomfortable truth is that the system was unstable from its inception and full implementation. There was no mechanism in place to constrain the supply of new currency creation, either from the government itself or by banks and their lending activities, despite the fact that the currency was backed by gold.

Lyn Alden, via officialdata.org

Dollar Reserve System (1974 to present)

In 1974, the dollar was flailing, but the United States had by far the largest economy and military, and thus had resources to fix it. The world had never been on a completely unbacked currency system all at once, so this was a new experiment.

The Nixon Administration made a deal with Saudi Arabia to backstop the dollar and reinforce its existing network effect worldwide. In this arrangement, Saudi Arabia would only sell its oil for dollars, regardless of who it was selling to, and would invest many of those dollar surpluses into U.S. Treasuries. In return, the U.S. would keep the agreement a secret (close association with the U.S. had troubling optics for Saudi Arabia so shortly after the 1973 Yom Kippur war) and would supply arms deals and regional protection for Saudi Arabia and their oil exporting infrastructure. This spread to the rest of OPEC, and the United States kept the dollar at the heart of the global financial system.

Most countries hold U.S. Treasuries as reserve holdings, and most developing countries rely on dollar-denominated financing (which is often lent to them from non-American sources, like European, Japanese, and Chinese lenders, in addition to American ones). In addition, most FX trading volume involves the dollar (currencies tend to get traded for dollars and then traded for other currencies, rather than traded directly), and a large percentage of international contracts are denominated in dollars.

However, this current system is unstable as well, in two ways.

Instability #1: Structural Trade Deficits

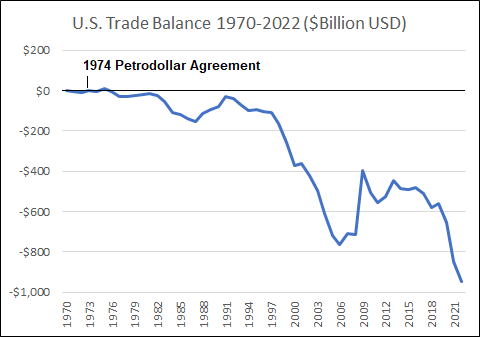

By reinforcing the dollar as the most salable currency with the deepest and most liquid capital markets, it attracts a strong monetary premium. Usually, currencies weaken when a country runs a trade deficit for too long, and strengthen when a country runs a trade surplus for a while. However, the U.S. dollar has a big extra monetary premium on it, which means it is stronger than it otherwise would be based on the U.S. trade balance. We therefore run trade deficits for decades straight, and the system doesn’t correct itself as most currencies would have done by this point:

Lyn Alden, via data from macrohistory.net

To put it another way, in order to supply the world with dollars, the United States needs to be in the dollar export business. And we do that via structural trade deficits.

The extra foreign demand for our currency strengthens our import power and weakens our export competitiveness, and so dollars continually flow out of the country to the rest of the world in the form of trade deficits. The rest of the world then takes their dollar surpluses and buys U.S. assets with them. They used to buy mainly Treasuries, but now they also buy equities, real estate, private equity, and other American assets.

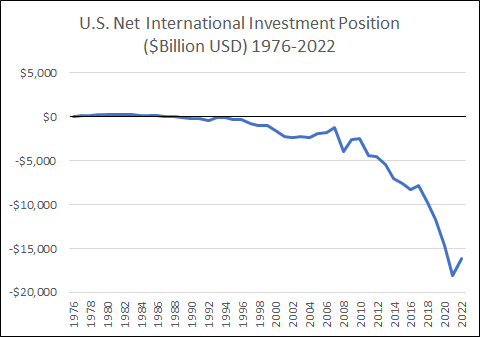

The U.S. therefore has a deeper and deeper negative net international investment position, meaning that foreigners own more U.S. assets than Americans own foreign assets.

Lyn Alden, via data from the IMF

A way to describe this is that the United States sells its appreciating capital (stocks, real estate, credit, etc.) in exchange for depreciating assets (electronics, industrial parts, raw commodities, etc.) in order to fund its trade deficit and maintain global reserve currency status, and the imbalance is unstable and thus keeps getting worse.

Instability #2: Rising Debt Levels

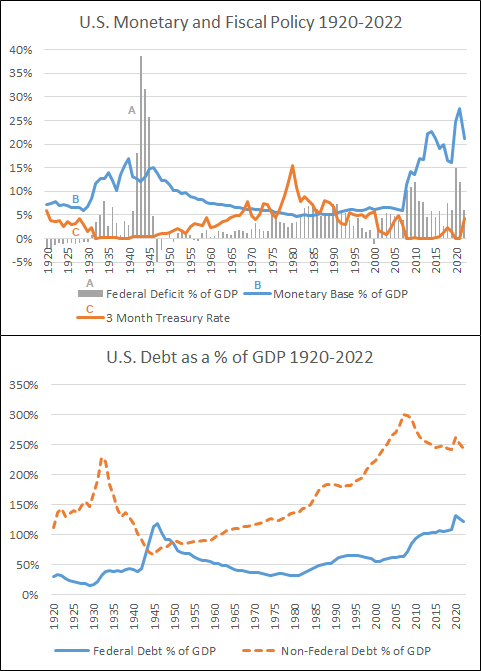

The prior point applied mainly to the United States, but this point applies to the U.S. and most developed countries. Sovereign debt levels relative to GDP keep increasing.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Fed Chairman Paul Volcker stabilized the dollar by sharply raising interest rates (along with the geopolitical maneuverings of getting OPEC nations to heavily invest in dollars in exchange for protection and arms deals). He was able to do this at the time because debt levels were quite low after so much inflation and defaulting and negative real interest rates.

This ushered in a four-decade trend of falling interest rates and rising debt levels. Whenever the U.S. economy ran into a slowdown, monetary policymakers would provide liquidity and cut interest rates. Fiscal policymakers would also generally provide stimulus.

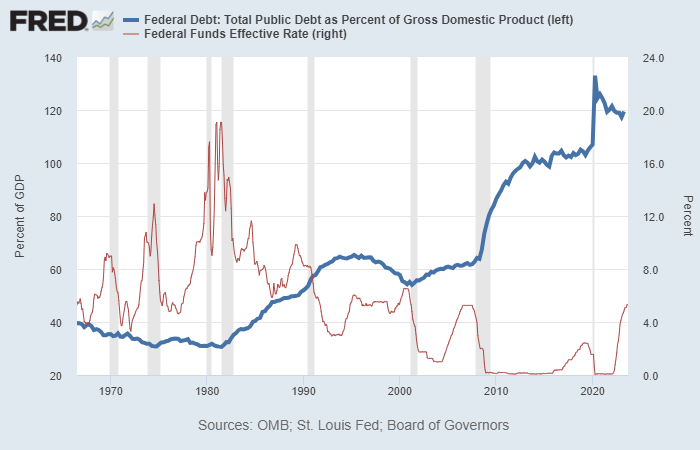

St. Louis Fed

The falling interest rates allowed for higher and higher debt accumulation without causing an acute problem, because interest expense remained low. If you double your debt level but cut your interest rate in half, for example, then your interest payments are unchanged. The United States benefited from that trend for forty years, and so countless calls for there being too much debt in the system came and went without issue. It lulled people into thinking the system was marginal or stable.

However, when interest rates bounce off zero and start going sideways-to-up, while deficits and debts keep growing, that’s a problem. The instability of the system begins to reveal itself.

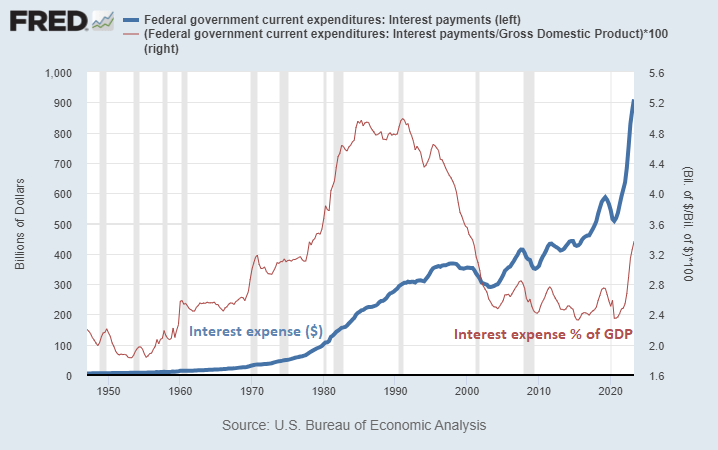

The United States now pays more money on its interest expense than it does on its entire military. The mid 1990s to the early 2020s saw a great moderation in interest expenses, and this coincided with the opening of the Soviet Union and China and consequently a large period of disinflationary globalization. That period is over now, both because we bounced off zero interest rates, and because the world has become more multipolar and adversarial.

St. Louis Fed

In a recent interview with CNBC, billionaire investor Paul Tudor Jones described the U.S. fiscal situation as follows:

You get in this vicious circle, where higher interest rates cause higher funding costs, cause higher debt issuance, which cause further bond liquidation, which cause higher rates, which put us in an untenable fiscal position.

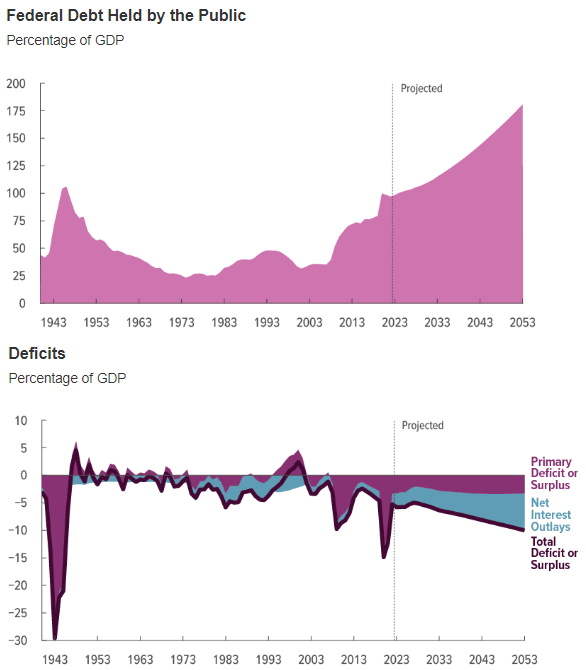

Here’s an image of the unbounded instability from the Congressional Budget Office, and this assumes that interest rates remain pretty low (it only gets worse if they remain high):

Congressional Budget Office

However, I differ from Paul Tudor Jones in terms of how I see this playing out in the years ahead. In the interview, Jones frequently said the United States is going to have to raise taxes and cut spending to get the fiscal situation under control. I view that as being very unlikely to happen in today’s polarized political environment.

-Republicans are likely to hold firm against tax increases.

-Democrats are likely to hold firm against cuts to entitlements.

-Most entitlements are inflation-adjusting. Social security is indexed to inflation, and Medicare expenses go up with the cost of healthcare.

-Military spending is unlikely to go down given the recent geopolitical situation. The U.S. is now financially involved in two war fronts, Ukraine and Israel, with Taiwan always a possibility as well.

-Tax receipts are highly correlated with asset prices in the United States because our economy is so financialized. Any fiscal actions that attempt to raise tax revenue but that dampen asset prices are likely to offset themselves.

So, in the long run, I expect this to lead to persistent above-target inflation or waves of inflation punctuated by temporary disinflationary slowdowns, driven by large monetized fiscal deficits.

Determining the Timing

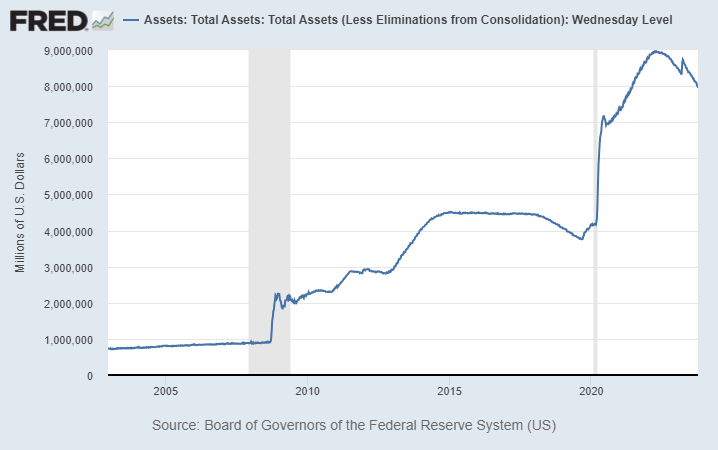

Currently, the Federal Reserve is trying to keep monetary policy tight to rein in inflation. High interest rates are having mixed results, as they slow down bank lending but also increase the fiscal deficit by quite a bit when debt levels are over 100%, which is stimulatory. They are, however, also reducing their balance sheet.

St. Louis Fed

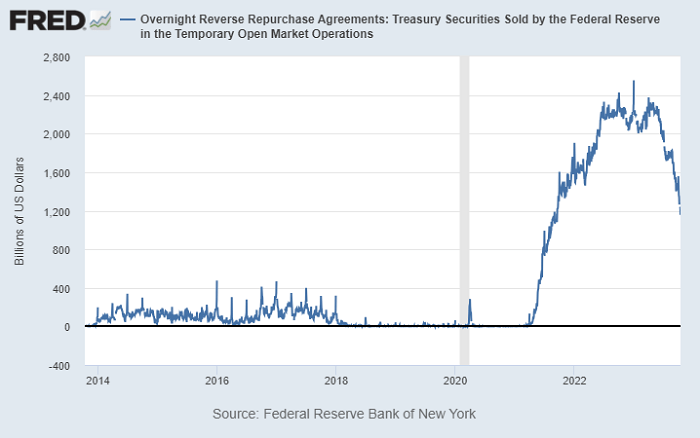

They’re able to decrease their balance sheet because, during their 2020-2021 stimulus, a huge reverse repo facility was built up. This can be thought of as a pool of excess liquidity that can be used to buy T-bills as they are issued. The liquidity in this reverse repo facility is now being used up and sent back into the rest of the financial system, and at the current rate will be drained in eight months or so:

St. Louis Fed

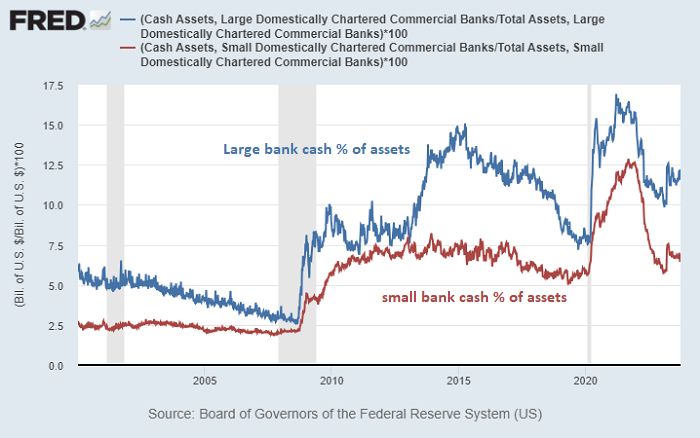

Bank cash levels as a percentage of total assets are also back down near their post-2008 effective limit. Ever since the March 2023 banking crisis, aggregate bank cash levels have been managed by policymakers with various tools to remain flat rather than keep going down as they were in 2022. Large banks could still draw down cash a bit more, but overall, there’s not a lot of room here.

St. Louis Fed

If the Fed finds itself in a position in 2024 where the reverse repo facility is drained and it has to stop decreasing its balance sheet and perhaps start increasing its balance sheet even if inflation levels are still above target, that could cause quite a change in market perception about the Fed’s ability to keep inflation under control. The market could collectively realize that the Treasury’s deficits are in control, not the Fed because someone needs to buy those Treasuries and keep the Treasury market functioning with decent liquidity.

From the 1990s through the 2010s, the world had a disinflationary “peace dividend” from the economic opening of China, the fall of the Soviet Union, and the resulting acceleration of globalization that ensued. Western capital and eastern labor were united, resulting in a huge increase in manufacturing in Asia. Russia began increasing its oil and gas production and supplying large amounts of cheap gas to Europe. As a result, unstable fiscal policies were easier to maintain, thanks to so much disinflationary pressure and new abundance, and the falling interest rates that this disinflation enabled.

In the 2020s, that era seems to be over. Large deficits and money supply growth are more likely to be “felt” quickly because there are fewer disinflationary offsets going forward. Technology will continue to provide some disinflationary pressure in the white-collar world, but the blue-collar world (energy, commodities, manufacturing, and trying to duplicate supply chains and make them more resilient) is likely to contribute to an inflationary backdrop, with uncontrolled fiscal deficits and the inability of central banks to deal with them with their policy tools, since their tools were designed to deal with excess bank lending, not excess fiscal deficits.

Final Thoughts: Life Goes On

When I talk about unstable financial systems up to and including the sovereign level of the developed world, it can come off as quite bearish. It sounds almost “doomy”.

But it’s important to remember that big monetary changes have happened before. Every few generations the system resets itself and starts something anew. The period of change can be disruptive, but on the other side, something comes out that is either better or worse, depending on how we all work together to shape it. To use the control system analogy again, the metal ball is picked back up and put back in the electromagnet control system.

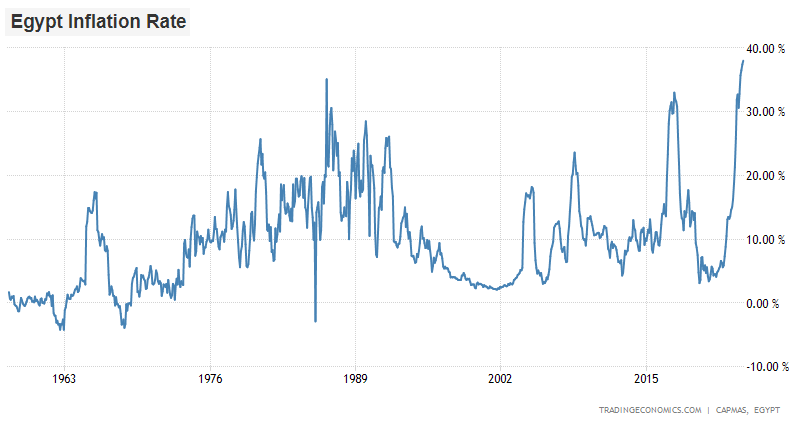

As a matter of perspective, I got back a few weeks ago from living in Cairo for a month and a half. My husband and I have family and friends there, and so we spend part of each year there. Egypt has less than $4k GDP per capita and was dealing with 37% record official inflation while I was there. And unfortunately, they are likely going to face another currency devaluation and a wave of inflation within the next year.

Trading Economics

And yet life… went on. People went to work. Kids went to school. Restaurants were full. Roads were packed. It’s hard there, but people are hustling. You wouldn’t guess that inflation was 37% by looking around. Life looks similar to how it looked last year, the year before, the year before, and so forth. The cracks are underneath the surface.

There are dark places out there where society fully breaks down. Incentives around the production of goods and services fall apart, people go hungry, and people flee. Fortunately, most countries are able to stabilize before they hit that type of situation, but it’s always a risk.

Those of us who are in some of the wealthier parts of the world should be grateful for our good fortune. Some of the worst financial situations in our countries are like a normal year in some of the poorest countries in the world. Things that seem unimaginable in the developed world happen all the time in the developing world.

I have a long-term positive view on gold and bitcoin given the prospect of fiscal problems ahead, but I also like T-bills, TIPS, oil producers, select real estate, select equities, and so forth. The past few years have been difficult for a lot of investors to navigate financially, with all sorts of “unprecedented” things happening that would have sounded crazy to someone in 2019. I expect the same will be true for the rest of the decade. We live in interesting times, but life goes on.

Editor’s Note: This article covers one or more microcap stocks. Please be aware of the risks associated with these stocks.

Read the full article here

Leave a Reply