Investment thesis

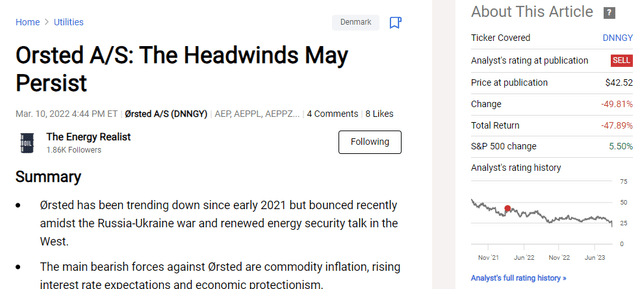

I looked at Ørsted A/S (OTCPK:DNNGY) (OTCPK:DOGEF) in March 2022 when I made a “sell” call based on the macro trifecta of commodity inflation, rising interest rates and economic protectionism:

Seeking Alpha

The stock is down 50% since and was already down 35% before Ørsted announced major impairments to its US portfolio this Tuesday, so I feel my bearish call has been justified thus far.

However, it puzzles me that as Ørsted was sliding down, Seeking Alpha analysts published 9 “buy”/”strong buy” and only 2 “hold” articles, without any new bearish takes, despite the multiple warning signs that offshore wind is currently not a healthy sector. A unifying theme across the bullish articles appears to be that Ørsted is somehow “undervalued” because it was trading at a higher price before.

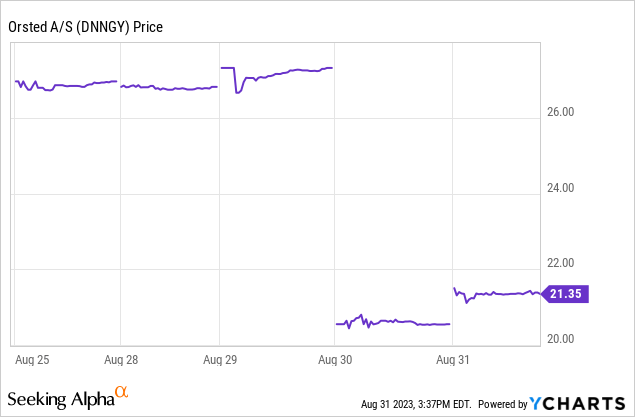

As Ørsted crashed 25% just in one day this week, I understand the temptation to “buy the dip”:

Eventually, one of the bullish calls will probably be right, but until then you can lose a lot of your net worth by trying to catch the proverbial “falling knife”, especially when the fundamentals are against you. So allow me to explain why 18 months later my bearish call on wind energy still stands and why thinking that Ørsted will allow you to profit from the energy transition is rather naive.

Rising interest rates are popping the “clean energy” bubble

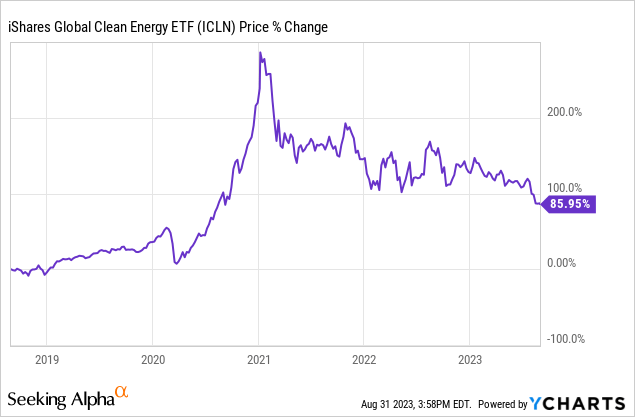

The main reason why wind and solar stocks are crashing is that, in the first place, they only went up so high due to the massive liquidity wave and zero interest rate policies unleashed by central banks during the pandemic. As liquidity tightened and U.S. rates are now above 5%, there has been a gravitational pull on long-duration stocks that promise to deliver cash flows far out into the future. In this regard, renewable energy is following the path of other Covid bubbles:

Note the iShares Global Clean Energy ETF (ICLN) is still up 86% from early 2020, which suggests the bubble deflation process may still have some runway left.

Moreover, high interest rates don’t just influence wind and solar stocks through the discount factor, but also have a direct impact on the attractiveness of project finance. For example, in a recent article, the Wall Street Journal reported that financing costs for solar projects had gone up by 30% compared to a few years ago due to higher interest rates.

The ESG heyday may be over

Without doubt, a second reason for the 2020-2021 outperformance of Ørsted and other renewable energy stocks has been the rise of the so-called ESG investing. ESG is hazy concept, but let’s say the idea behind it is that fund managers should be scored not just on the returns of their portfolio but also based on the extent to which their holdings contribute to environmental and social goals, including, of course, de-carbonization.

ESG investing has had important repercussions across the investment industry, including:

- Increased cost of capital for “traditional energy” players involved with fossil fuels, as fund managers avoid these investments to prevent their fund ESG scores from falling;

- Reduced cost of capital for “new energy” companies like Ørsted, as funds are incentivized to own stocks that improve their ESG score, even if they don’t necessarily buy into the soundness of the business model.

Proverbially, you know that a new trend is over when one of the major business magazines proclaims it is going to be the future “forever” and with ESG investing I think we reached that point 1-2 years ago:

Forbes

The linked Forbes article cites a PwC prediction that ESG-oriented assets under management are to:

“more than double” in the United States to $10.5 trillion; to rise 53% in Europe to $19.6 trillion; and, to more than triple in the Asia-Pacific region to $3.3 trillion in 2026.

One should approach studies sponsored by consulting firms with similar skepticism as the business magazine covers. Ultimately, consultancies are trying to sell more of their services and are tailoring their marketing message to the dominant trend, but that by itself is also a lagging indicator.

So what is the leading indicator then? I think it could be Larry Fink, the head of BlackRock (BLK), which is the world’s largest asset manager, backtracking on whole the ESG investing idea, as featured here:

[Fink] now refuses to use the word “ESG” any longer, saying “it’s been misused by the far left and the far right.”

“I’m not blaming one side or the other, but it has been totally weaponized,” Fink said Sunday at the Aspen Ideas Festival, according to media reports.

It seems that we now even have anti-ESG funds. It’s not a perfect indicator, but when someone creates an inverse ETF, it usually indicates there is already sufficient interest in the contrarian thesis.

So long story short, I think the times are changing (again) and I see a strengthening push towards evaluating investment performance based on more traditional metrics. Ørsted can ring the carbon alarm bell as much as it likes (see my comments on their earnings call below), but unless they start generating tangible returns, investors may keep them in the penalty box.

“Dirty energy” scarcity makes “clean energy” expensive

One of the greatest paradoxes in the renewables landscape is that building out the infrastructure requires a lot of traditional energy. To quote from my prior article:

According to the U.S. Geological Survey, wind turbines typically consist of:

steel (66% to 79% of total mass)

fiberglass, resin or plastic (11% to 16%)

iron or case iron (5% to 17%)

copper (1%)

aluminum (0% to 2%)

Fossil fuels aren’t a direct input but definitely an important indirect one as producing materials such as steel is very energy intensive. So is metals and mining in general. Copper is a small portion of the windmills, but new windfarms, especially offshore, require significant investments in electrification that are also copper dependent.

As ESG investing has starved the traditional energy and mining sectors of capital, the costs in these sectors have risen, and this is pushing up the commodity price itself. Ironically, more expensive commodities increase the construction costs for offshore wind and others.

Governments heeding Ørsted’s call for more subsidies (see below) may not be a long-term solution either. These subsidies will be paid out with fiat money, thus fueling the already high inflation. When inflation is high, commodities often appreciate as they act as a hedge. So each way you look at it, something’s gotta give.

Deglobalization doesn’t make it easier

If you want to invest in wind, you have to mind the geopolitics. Initially, supply chain disruptions were driven by the pandemic, but now a big problem are the deteriorating U.S.-China relations. If you want to onshore to the U.S., where Ørsted’s most problematic developments are, costs will be higher.

The Build Back Better Act (which I didn’t believe would pass when I wrote my prior article) is supportive from investment credit perspective, but also adds a lot of preferences for U.S. generated content (the “economic protectionism” piece of my original thesis).

The Wall Street Journal lays out this nicely:

The U.S. has other challenges, including policies that make it harder and more costly to import solar panels and other clean-energy components. Rising labor costs and delays in permitting or getting projects hooked up to the power grid have made building solar and wind projects more expensive.

Whichever way you look at it, this is not bullish.

Wind’s problems have gone mainstream

There is certainly something to be said about the “price driving narrative” concept, but at this point there is no shortage of reporting about the problems in the wind industry.

Ørsted’s impairments aren’t an isolated incident. According to the WSJ again:

Norway’s Equinor and Britain’s BP are developing three wind farms off the coast of New York and said in June that they will need to renegotiate power prices or the projects won’t get financing, while a subsidiary of Spanish multinational Iberdrola last month agreed to pay $48 million to back out of an offshore wind-power deal in Massachusetts that it bid in September 2021, when project economics were more favorable.

A first-ever auction of offshore wind development rights in the Gulf of Mexico resulted in a single $5.6 million winning bid on Tuesday, while two areas offshore Texas that were offered received no bids at all.

The culprits, again, are rising interest and materials costs, and there is no indication how these trends would be countered. I am afraid Seeking Alpha’s bullish analysts aren’t sufficiently educating the reader about these structural issues. There may be a time to be “contrarian” but it’s not now when this is just starting to play out.

Unreliability issues have hit the value chain

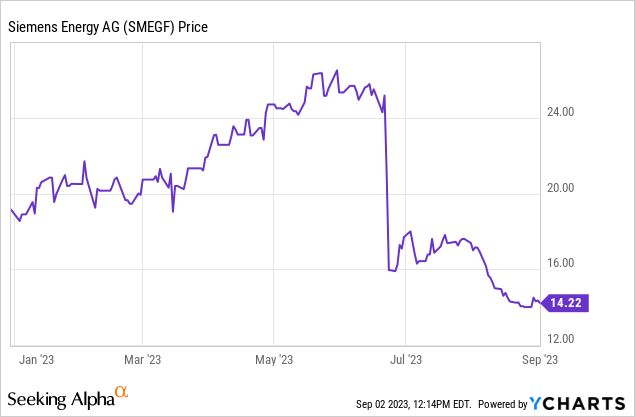

The wind turbine manufacturers delivered quite a bit of bad news this year too. Siemens Gamesa (OTCPK:SMEGF) was among them:

In the WSJ’s reporting, “shares plummeted Friday in early trading [in June] after the German energy company withdrew its fiscal 2023 profit guidance following a technical review of Siemens Gamesa’s installed fleet and product designs.” According to the analysts cited in the linked article:

The group [Siemens Energy] is seeing worse failure rates on specific wind turbine components than initially expected leading to higher costs for repair over coming years. This will also likely impact cash over several years.

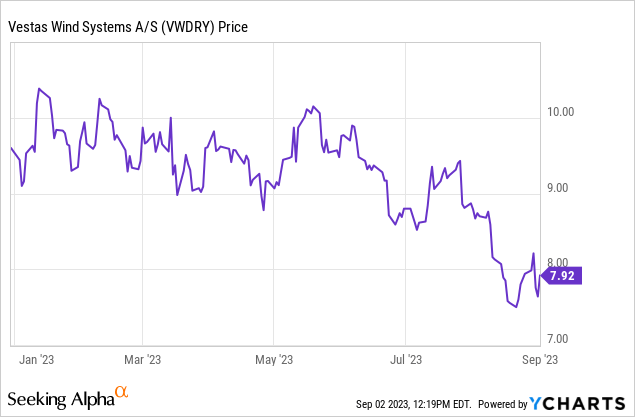

Vestas (VWDRY), another big manufacturer, hasn’t been spared either from the concerns over quality:

Admittedly, Ørsted is on the customer side here, but these manufacturing quality issues will undoubtedly also affect the company’s execution timelines.

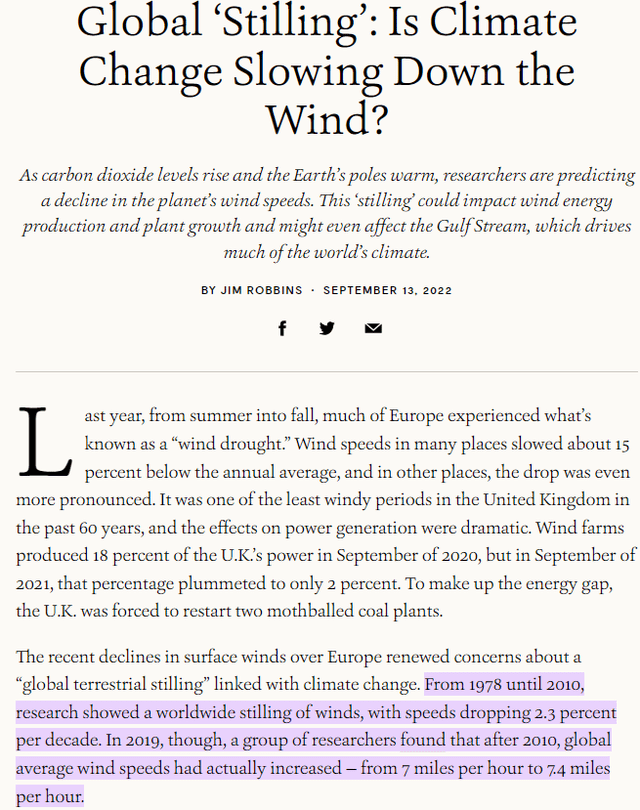

Wind may be slowing too

There is a lot of debate on slowing wind speeds, also known as “stilling”:

Yale School of the Environment

I wanted to mention this even though it isn’t a central piece to my thesis. My view is the evidence appears a little mixed, and, even if ultimately corroborated, this is something outside management’s control. However, a robust procurement strategy that can mitigate the rising costs is under Ørsted’s control and should be expected of management.

Seeking subsidies

Unfortunately, instead of offering a more introspective look at the company’s difficulties, Ørsted’s CEO opened the latest earnings call by essentially asking governments (ultimately, the taxpayer or “you”, if you reside in a “Western” country) to pick up the tab for the increased costs (my highlights):

I would like to touch upon the numerous extraordinary weather events relating to climate changes across the globe that we’ve seen over the past months, including 17 straight days with global temperatures hotter than any prior days on record. These events have once again illustrated the fact that urgent investments are needed into green transformation of the world’s energy systems and that they are needed more than ever. Let me reiterate how vital it is that governments and decision-makers around the world address and reduce the industry risks facing the renewable sector. The offtake frameworks and contracted power prices must reflect the realities of the inflationary environment within the renewable sector. Otherwise, the necessary investments in renewable energy are at risk of either slowing down or simply not happening.

An engineering company that is building, say, an airport or a highway under fixed parameters would be expected to eat up the cost overruns, but Ørsted effectively argues it should be insulated from any downside (while retaining the upside!) because of the “climate emergency.” Climate at the end of the day is still a public interest project and the rules followed by private operators who execute with public funds should be consistent regardless the cause.

Ørsted’s focus on more subsidies as the “solution” is also emphasized in the official impairment release:

Our continued discussions with senior federal stakeholders about additional ITC [investment tax credits] qualifications for Ocean Wind 1 and Sunrise Wind are not progressing as we previously expected. We continue to engage in discussions with federal stakeholders to qualify for additional tax credits beyond 30%. If these efforts prove unsuccessful, it could lead to impairments of up to DKK 6 billion. The level of a possible impairment will be decided based on a probability weighted assessment of the likelihood of obtaining the additional ITCs.

This raises some interesting questions because Ørsted remains majority owned by the Danish government. The U.S. Federal and the affected state governments bending their rules to ultimately benefit a foreign government (according to the WSJ, Ørsted wants us a bump from the 30% ITC to “at least 40%”) may draw quite some scrutiny as the U.S. is headed into an election year.

I don’t know how this will play out, but my feeling is the U.S. political calculus may not be the most favorable for meeting Ørsted’s demands this time around.

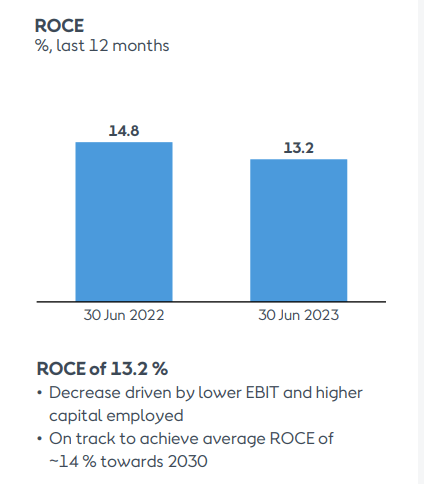

Cash flow remains negative

Ørsted’s favorite performance measure appears to be ROCE (return on capital employed). As reported in the investor presentations, it may be quite high at 13-14%:

Ørsted Investor Presentation

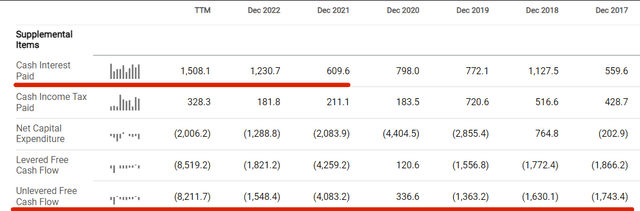

However, ROCE can be a bit misleading for cash-negative companies and Ørsted’s cash flow has been negative all along:

Seeking Alpha

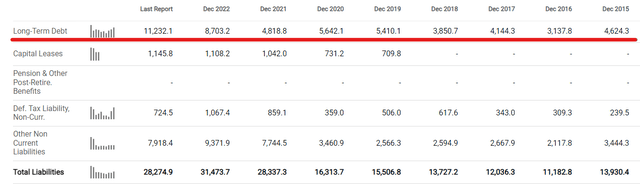

The capital expenditures are financed by debt, which has steadily increased:

Seeking Alpha

Cash interest expense is trending up – not only is debt growing but so are the interest rates at which new financing can be obtained.

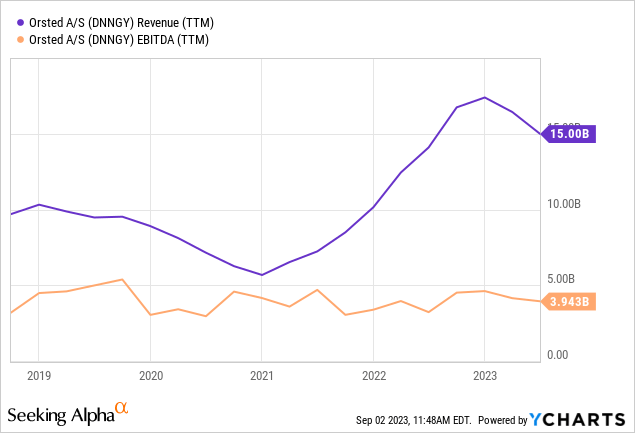

Typically, the rationale for investing in a cash-negative company is the growth, which would translate into positive cash flow further down the road. However, Ørsted’s isn’t exactly “growing”:

Revenue peaked recently because of the windfall component from the surge in European electricity prices which wasn’t sustainable. However, even during that period, Ørsted hasn’t able to increase EBITDA which has now flatlined for the last 5 years.

The valuation is still rich

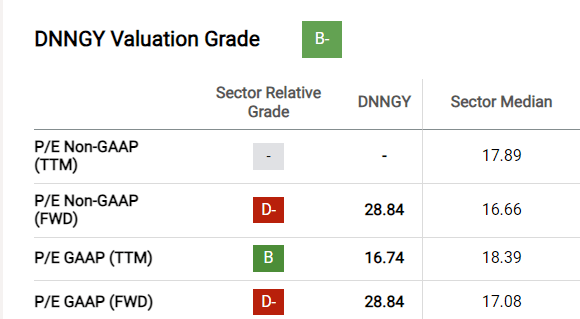

Seeking Alpha’s “B-” valuation score may mislead you into thinking Ørsted is a value opportunity.

Seeking Alpha

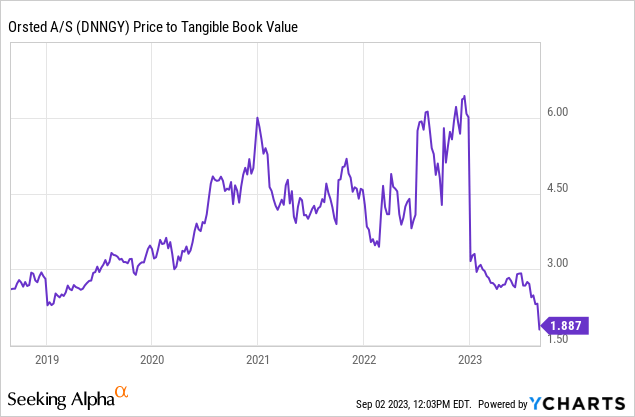

At 28x forward earnings, Ørsted is hardly “cheap.” The price to book ratio has indeed moderated quite a bit:

However, remember that the book value doesn’t yet include the impairments which triggered the selloff on Tuesday. Once those impairments are recorded, the book value will decrease and the ratio will rise again.

In summary, nothing here screams “value”, especially when considering the deteriorating performance. Rather, I would argue we have an instance of a “bubble” gradually normalizing.

Ørsted is a poor choice to profit from the energy transition

I already explained how ESG mandates may have influenced institutional investors to add Ørsted to their portfolios. As for retail, from perusing some of the other articles and comments under this ticker, I get the sense that some bought into the logic that the green energy trend will be good for green energy producers. This is a naive view that ignores the second-order effects I have explained here.

In my view, what defines an attractive industry is control over scarce resources that act as “moat” and provide pricing power. The wind developers like Ørsted aren’t on the good side of this equation. Pricing is based on offtake agreements with government entities and, as argued, I see little appetite for unlimited subsidies.

Ørsted also has little protection from the commodity inflation that increases the cost of its inputs. The contrarian view here isn’t to “catch the falling knife” but rather to look further upstream along the value chain where the producers of metals and critical minerals will be able to charge higher prices for their outputs as the energy transition boosts demand.

I mean, if you bother to read between the lines, even Ørsted itself told you where to look for above-market return opportunities:

The company is facing delays from suppliers, mainly from companies that build the offshore foundations as well as from a specialist installation vessel, which could create knock-on effects for final installation as well as potentially delaying revenue and increasing costs.

I couldn’t track down which is the specific installation vessel in question, but it sounds like offshore services is acting as the bottleneck here. The wise thing would be to consider investing in these offshore providers whose services are obviously in high demand.

In fact, I have argued before that offshore services providers like Tidewater (TDW) or Oil States International (OIS), among multiple others, may be surprising winners of the energy transition as they support both oil and offshore wind developments and are currently capacity constrained. So the bottom line is if you want to capitalize on green energy, you need to think a bit outside the box and not just buy the first thing that has “green” (figuratively speaking) in its name.

Bottom line: Stay away

The headwinds of high interest rates, commodity inflation, supply chain bottlenecks and geopolitical issues that drive “de-globalization” are hurting offshore wind big time. Add to that the reliability issues reported earlier this year by the wind turbine manufacturers and you don’t get a very pretty picture.

Ørsted so far isn’t showing it has a plan to navigate these challenges except asking governments for greater subsidies. I think the political environment, especially in the U.S. where Ørsted’s impaired developments are, isn’t currently conducive to these demands as inflation is clearly a bigger priority for voters (granting the company’s demands would actually be inflationary).

That is why I recommend against investing in Ørsted and waiting for the wind bubble deflation to fully play out. When that happens, Ørsted may perhaps present a value opportunity, but that time hasn’t arrived yet.

As closing words, I will also emphasize I am not short Ørsted and I don’t necessarily recommend shorting the stock. The Danish government may at some point provide a backstop if things go really bad, and even the 50% slide since my last article was marked by a number of counter-rallies that can wipe out your short position.

As always, do your own due diligence.

Editor’s Note: This article discusses one or more securities that do not trade on a major U.S. exchange. Please be aware of the risks associated with these stocks.

Read the full article here

Leave a Reply