Investors in contingent convertible (CoCo) bonds had a wake-up call during the banking crisis of March 2023. Swiss regulators fully wrote down Credit Suisse CoCo bonds as part of the merger with UBS, wiping out the investment despite Credit Suisse not technically defaulting [1]. This event highlights the need to properly understand the risks with these bonds.

A CoCo bond is debt issued by a bank that contains a trigger that will either write down the bond’s face value or convert the bond to equity. The trigger occurs when the bank’s Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) capital drops below a specified level, or at the discretion of the bank’s regulator. By reducing debt or increasing CET1 capital, they can improve the financial health of the bank when in stress. While the investment may behave like a bond under normal market conditions, investors may find themselves playing the role of bank savior when a crisis hits.

CoCo bonds are relatively complex instruments. They are normally perpetual and after an initial fixed rate period switch to floating. After the switch, the bonds are typically callable by the issuer. These bonds are subject to interest rate risk, as well as the risk of loss of principal upon trigger. The bonds also have extension risk, which is the risk that the issuer will not call the bond, leaving the investors holding a bond with no set maturity and paying market rates. When the health of the bank deteriorates, the bank is unlikely to call the bond, as refinancing on good terms will be difficult. Extension and trigger risk can therefore compound each other, leaving the investor holding an instrument that isn’t beating market yields while having high risk of loss of principal.

Accurately modelling the conversion option can be difficult, as the trigger depends on the bank’s capital levels or on the subjective behavior of the regulator. While bank capital levels are published quarterly, they depend on various factors that are difficult to model, and there is no option market from which to infer implied volatility of the capital. And of course, regulatory decisions like in the case of Credit Suisse are difficult to model quantitatively. It is therefore common to model the conversion as occurring when the bank’s equity price hits a specified trigger price. With this assumption, the techniques of equity barrier option pricing can be used to model CoCo bonds [2].

Modelling CoCo bonds

Modelling the CoCo bond trigger option as an equity barrier option requires knowledge of the equity price, equity volatility, and the trigger price. The equity price is readily available in the market. Equity volatility is as well, however, as discussed in Corcurea, De Spiegeleer et al., [3] the barrier option that models the trigger is struck deep out of the money and may be long-dated. Sufficiently long-dated, deep out-of-the-money equity options are not very liquid, so it may be more appropriate to calibrate volatility to the CDS market. This is done by noting the protection leg of the CDS is approximated by a digital down-and-in barrier option for a very low barrier level. We take this approach in the analysis shown below. Deriving volatility from the CDS market allows the pricing of the CoCo bond to be sensitive to the CDS market. The probability of trigger then reacts to widening credit spreads, as one would expect, even if the stock price is not yet pricing in the elevated risk of the bank. With knowledge of the equity price and volatility, the trigger level can be calibrated to CoCo bond prices.

It is also common to model perpetual fixed-to-float bonds as maturing on the switch date. However, as discussed in De Spiegeleer and Schoutens [4], as well as in our own analysis [5], this is a dangerous assumption as the bank’s incentive to call is a function of the credit spread of the bank. For a CoCo bond, the credit spread is synonymous with CoCo spread and grows as the equity price approaches the trigger price, or as the bank’s CDS spread widens. Therefore, in periods of stress, the CoCo bond becomes susceptible to both conversion risk and extension risk.

Below, we analyze risk on a portfolio of six CoCo bonds. We chose six bonds issued by six different issuers: Credit Agricole (OTCPK:CRARF), Deutsche Bank (DB), Santander (SAN), Lloyds (LYG), BNP (OTCQX:BNPQF), and Societe Generale (OTCPK:SCGLF). The risk is quantified by computing the P&L distribution on 31 March 2023 using 1 year of historical daily returns. This includes the period of the bank crisis in March 2023.

The three models considered are as follows:

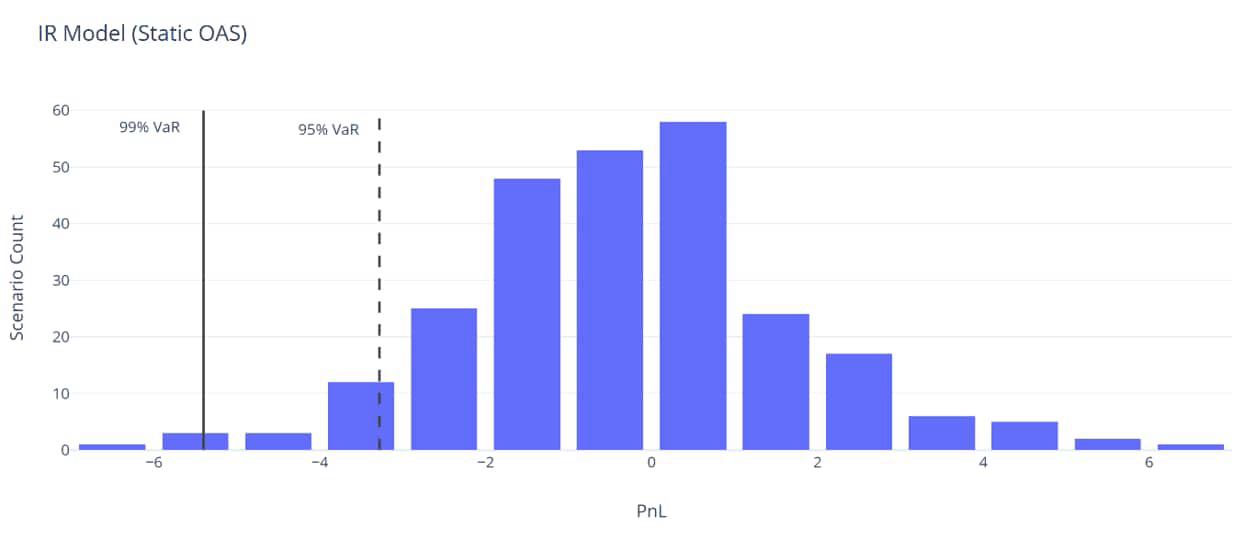

1. IR: This model treats the CoCo bond as a fixed-to-float callable bond with static Z-spread. It effectively ignores conversion and captures only interest rate risk in the P&L.

Figure 1: P&L distribution for the IR model. 99% 1-day value at risk (VaR): 5.4 EUR, 95% 1-day VaR: 3.3 EUR.

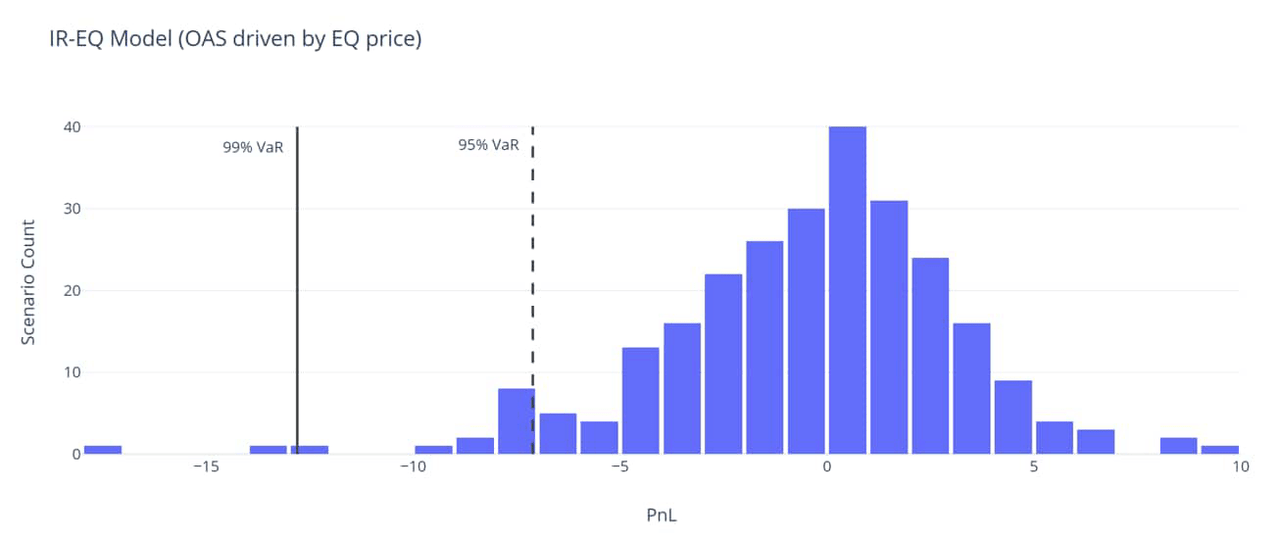

2. IR-EQ: This model replaces the static Z-spread with an equity price-dependent CoCo spread modelled as an equity barrier option.

Figure 2: P&L distribution for the IR-EQ model. 99% 1-day VaR: 12.8 EUR, 95% 1-day VaR: 7EUR.

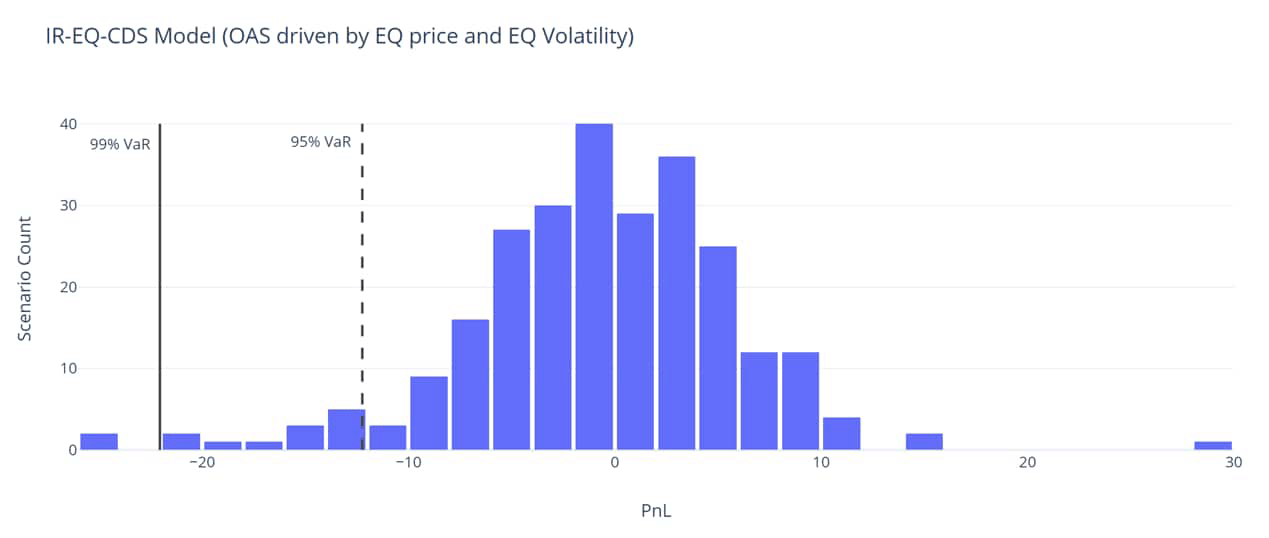

3. IR-EQ-CDS: This model extends model 2 to include shocks from the CDS time series that impacts our equity volatility.

Figure 3: P&L distribution for the IR-EQ-CDS model. 99% 1-day VaR: 22.05 EUR, 95% 1-day VaR: 12.24 EUR.

Comparing the models

In models 2 and 3, we can confirm the tail of the P&L distribution is made up of the scenarios of March 2023. A comparison of models 1 and 2 shows that CoCo bond risk in periods of stress deviates significantly from that of a callable bond without conversion risk, and it is critical to directly model the trigger in stressful periods. Focusing on a single bond, we study its price as a function of equity price in Figure 4. As the equity price drops toward trigger, the bond price decreases due to the higher risk of trigger. The sensitivity to the equity price (slope) also increases as the equity price drops, reflecting the higher risk in the bond.

As noted earlier, extension risk (the risk the issuer will not call the bond on the first call date) in these fixed-to-variable bonds is largely determined by the credit spread of the issuer, or in the case of the CoCo bond, the CoCo spread. With the goal of assessing extension risk, we plot the red line, which consists of modifying the original bond (in blue) with a very high step-up rate after the switch coupon date (the date a fixed coupon turns into a floating coupon). This effectively acts as an incentive for the issuer to call the bond at the first opportunity, which is the switch date. As a result, we have removed any possibility for this bond to extend further than the first call date. The two bond prices differ at a low equity price, and we note that the bond with the correct modelling of extension is riskier. As the equity price drives the CoCo spread, at the separation point, the spread has become too large for the issuer to consider calling it in the blue scenario. This extension risk results in the steeper decline in bond price as the equity price approaches trigger.

Figure 4: Bond price impact after adding equity risk factor.

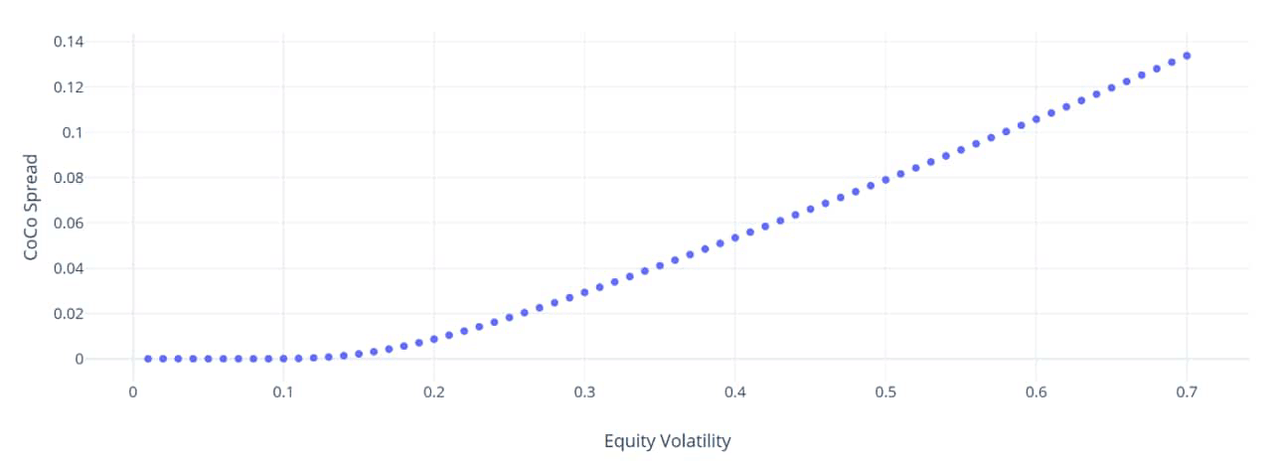

A comparison of models 2 and 3 demonstrates the impact of market-implied risk of conversion. As CDS spreads spike in the period of stress, the market’s expectation of default drives the volatility of the equity and thus the likelihood of trigger to occur. This internally brings down the bond price further. We plot in Figure 5 the CoCo spread as a function of equity volatility. The spread increases with the equity volatility increasing, which yields lower bond prices.

Figure 5: CoCo spread as a function of equity volatility.

Capturing conversion risk

The results presented here illustrate the importance of capturing conversion risk during periods of stress. Modelling conversion risk as a function of both equity price and CDS spread, the CoCo bond prices reflect the market’s implied probability of conversion. A drop in equity increases the probability of conversion leading to a lower bond price. Similarly, with widening credit spreads, we expect a higher equity volatility, which in turn leads to decreasing bond prices. Additionally, extension risk can add risk to the CoCo bond. As the CoCo spread widens in periods of stress, the incentive for the user to call drops, increasing the risk to the investor. Investors will want to ensure they are capturing all inherent risks in their CoCo bond portfolio ahead of the next banking crisis.

References

[1] Alexander P, Mourselas C, Clancy L, Rhiruchelvam S. How Finma milked Credit Suisse’s CoCos to close UBS deal. Risk.net, 21 March 2023.

[2] De Spiegeleer J, Schoutens W. Pricing contingent convertibles: A derivatives approach. SSRN, June 2011.

[3] Corcurea JM, De Spiegeleer J, Ferreiro-Castill A, et al. Efficient pricing of contingent convertibles under smile conforms models. SSRN, November 2011.

[4] De Spiegeleer J, Schoutens W. CoCo bonds with extension risk. SSRN, February 2014.

[5] S&P Global. Understanding extension risks of fixed-to-variable bonds. 2023.

Original Post

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.

Read the full article here

Leave a Reply