Introduction

While it is always the case that it’s wise to watch what a person does as much as listen to what they say, it was more important than ever at this year’s annual Berkshire Hathaway Inc. (NYSE:BRK.A, NYSE:BRK.B) meeting. Even though I’ve been a Berkshire shareholder for many years, I don’t write many articles about the company because there is already a lot of coverage from other analysts. I prefer to only write about Berkshire when I have something different to add.

Last year, I wrote an article about the five most important themes from the Q&A portion of the annual meeting, and that article was well-received by readers. The response has prompted me to write an article about this year’s meeting as well. And this year, there was a single theme that connected and ran through most of the important topics discussed: Political Risk.

Political risk has been a topic in previous meetings as well. One of my themes from last year was the relationship between business, society, and government (aka, politics). But this year, in terms of importance, political risk dominated most other topics.

There are two paradoxes CEO Warren Buffett faces when it comes to sharing investing wisdom and political thoughts. He can’t (or won’t) share specific investing reasons and explanations of current or recent holdings because his competitors can and will use that information for their own benefit, potentially harming Berkshire and its shareholders. So, on one hand, it is not to the benefit of Berkshire shareholders for Buffett to share this sort of information, while on the other, some shareholders will ask for it at the annual meeting anyway and expect an answer. Buffett has been adept at finding a balance with his answers over the years, but ultimately investors need to learn to read between the lines and use their own judgment regarding his investing motives and processes because Buffett doesn’t usually share the details.

The political paradox is similar to the investing information paradox, but slightly different. For many years, Buffett was more open about certain political and public policy opinions, but for the last several years he has avoided expressing those views for fear there could be repercussions for Berkshire’s shareholders and employees. In normal times, expressing his views wouldn’t be too much of an issue, but we are now in times when Berkshire’s biggest potential threats are rooted in politics and government policy. When we take these two paradoxes together, it severely limits what Buffett feels he can safely say at the annual meeting without damaging Berkshire. This means investors need to do more of their own work to figure out what Buffett is trying to communicate.

In this article, I will share my interpretation and takeaways from the meeting. While I don’t claim to have definitive answers and certainly don’t claim to speak for Buffett, I hope that I at least give investors a perspective to think about and discuss. I will share three different types of political risk, what those risks could mean for investors, and what I am doing about it personally in my investing strategy.

Three types of political risk ran through most topics: regulations, taxes, and geopolitical change. I’ll address them in that order.

Political Risk #1: Regulations

The biggest regulatory risk came via the potential liability issues caused by wildfires, particularly in California and Oregon. This topic was noted in the annual letter to shareholders as well. Buffett admitted that this was not a risk he anticipated when Berkshire got into the utility business. He pointed most of the blame toward climate change, but the message should have been clear to Western state legislatures and regulators that if they wanted private capital to help build the necessary electricity infrastructure in the future, either changes in the regulations or interpretation of those regulations would need to happen. In his words, he is “not going to throw good money after bad.”

At the meeting, Utah’s policies were shared as an example of a way to structure better policies and regulations. It will be very interesting to see how this evolves. I think Berkshire is being very reasonable, but it’s difficult to tell nowadays how reasonable politicians will be. At any rate, the risk here to Berkshire is ultimately political in nature, and very difficult to quantify.

What it could mean for investors

For what it’s worth, I think Berkshire Hathaway Energy is probably the best utility business in the country. So, if this issue is affecting them enough that they might get out of the business, or at least not invest more into it, investors who own other utility stocks should consider the risk they might be taking on as well.

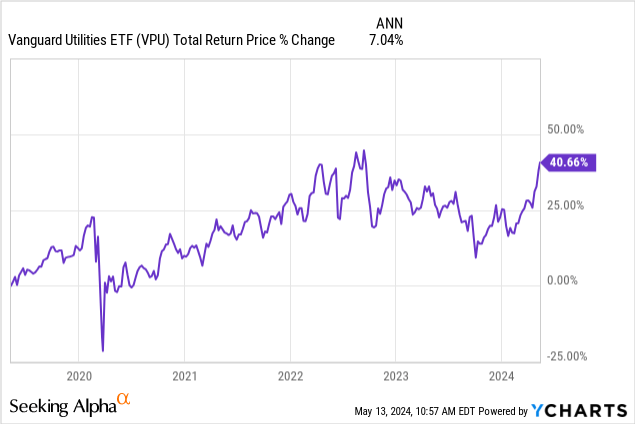

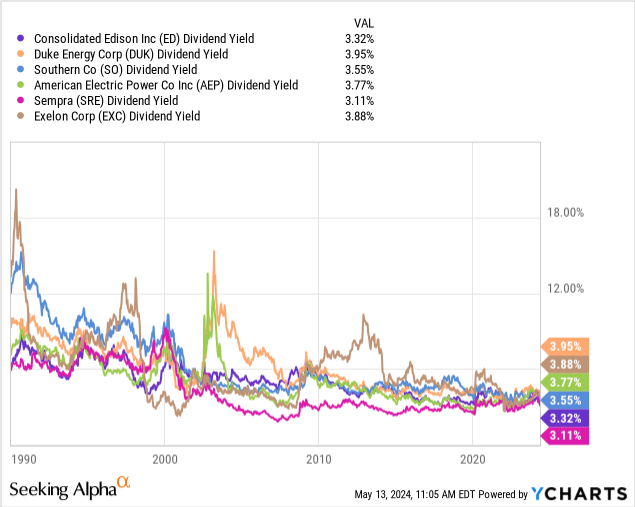

Utility stocks have only produced about a 7% CAGR over the past 5 years, but have rallied a lot this year. The valuations of the utilities I actively track are already extremely high. The dividend yield of the Vanguard Utilities Index Fund ETF Shares (VPU), which has an inverse relationship to the valuation, is only about 3%. Basically, in line with inflation. So, utilities on average currently yield nothing in real terms.

Above are the historical dividend yields of several of VPU’s top holdings. All of them are under 4%.

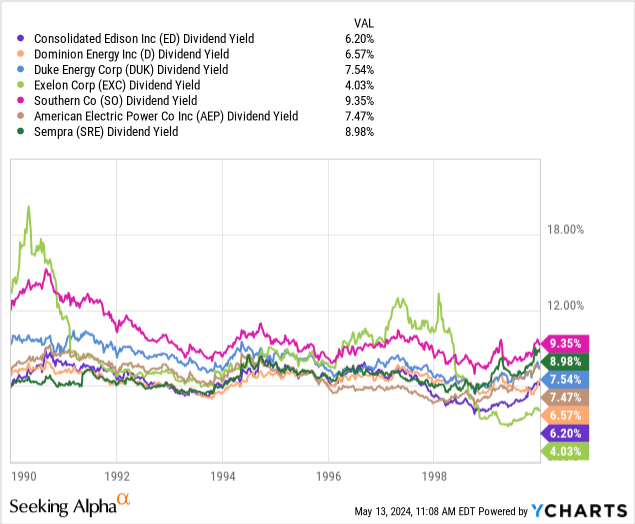

Contrast the current dividend yields to those in January 2000. Their yields back then were typically double what they are right now. So, not only do utilities probably have more political risk in certain situations, they are also costly right now relative to history.

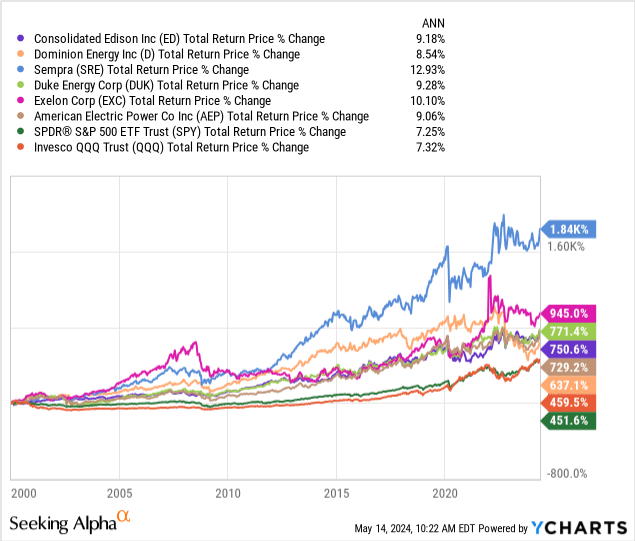

When purchased at good valuations as they were in 2000, utilities can produce very good returns. The group of utilities I shared earlier significantly outperformed both SPDR® S&P 500 ETF Trust (SPY) and Invesco QQQ Trust ETF (QQQ) over the past 24 years, as we can see in the chart above. This is not the situation with the valuation of utilities right now, though, and investors should expect moderately high risk with low returns over the medium term.

What I’m doing

While I do track several of the utilities above, because of the high valuations and low dividend yields relative to inflation, combined with additional political risks, I don’t own a single utility stock.

Political Risk #2: Higher Taxes

Buffett also mentioned the possibility that due to federal government deficits, we shouldn’t be surprised if taxes rise in the future. He pointed out that taxes had been significantly higher in the past. In my view, this was mostly a bit of a deflection from speaking more directly about his sale of some Apple stock, but, I think in the big picture he is correct about the risk of higher taxes in the future.

Basically, what we have done in the U.S. over the past 30 years is to suppress the wages of workers and the profits of domestic businesses by allowing nearly unfettered competition from cheap labor in lower regulatory regions of the world like China. To reduce the burden of lower real wages for the U.S. citizens whose jobs were moved out of the country, taxes have been lowered considerably over the past 20–25 years, book ended with GW Bush’s cuts around 2002 and Trump’s in 2018. Interest rates were also lowered. Government spending increased as well. The result was Americans got cheaper goods manufactured overseas, multinational corporations grew profits, and financial assets had a record bull market.

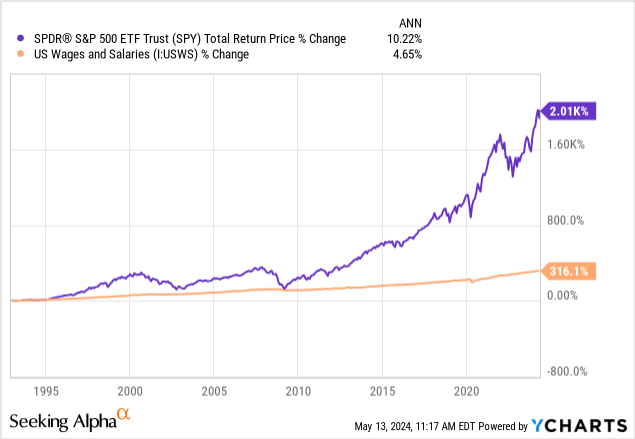

The above chart shows the rise in the S&P 500 (SP500) compared to US Wages & Salaries starting soon after the NAFTA agreement was signed in 1992. The biggest U.S. businesses have produced more than double the long-term CAGR of U.S. wages.

This article is not a normative essay about the fairness or unfairness of this situation. It’s simply sharing what has happened because this trend is likely to change soon and that will certainly affect businesses and investors, particularly those relying on certain international markets.

What this could mean for investors

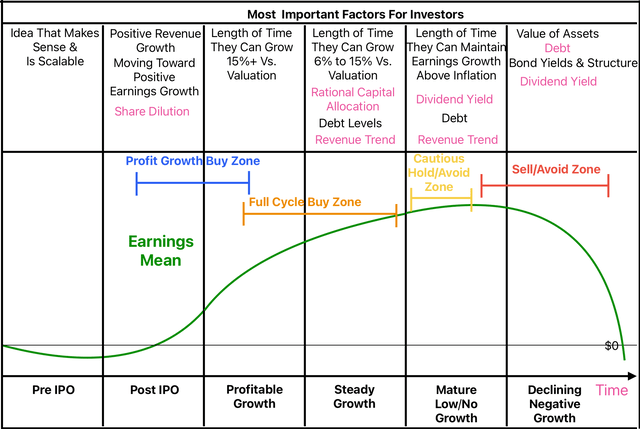

I think investors should make sure they aren’t letting the prospect of paying the current long-term capital gains tax rate prevent them or deter them from selling the stocks of businesses that are in the later stages of the business lifecycle. Below, I have created a graphic to show the stages of public businesses.

Cory Cramer

The time a business spends in each zone can vary. I would put Berkshire in the Steady growth stage because they can still grow earnings in the high single digits. But there are many other stocks investors might have held for a long time that are in or entering the No Growth, or Declining Growth Stages. Just as Buffett sold some Apple (AAPL) stock, now might be the time for investors to sell the stocks of these later-stage businesses if the only reason they continue to hold on to them is they don’t want the capital gains tax bill.

There are a couple of reasons for this. The first is that the stocks will probably lose more value over time than the tax will cost to sell them. But the second is that if an investor was planning to hold until death and step up the cost basis for their heirs, I think one of the easiest tax loopholes to justify closing is the stepped-up cost basis because a politician could do it without ever “raising taxes” and it only affects a relatively small portion of the public who own stocks in a taxable account with big unrealized capital gains. It seems like an easy target for the government to raise revenue. To make this danger even higher, it’s possible capital gains taxes could rise as well.

Whenever I write articles about taking profits in overvalued businesses or businesses that aren’t growing much anymore, often readers will quote Buffett about “the best holding period being forever.” But we see with Buffett’s sale of Apple that it is not the case that Buffett never sells.

What I’m doing

Interest rates are now higher. Taxes are set to rise somewhat in 2025 for individuals. The deflation caused by increased international trade is reversing. I think Buffett is correct to anticipate a change at some point in the future regarding tax rates for businesses as well. What form that will take exactly is difficult to predict. Even if I thought we could predict the outcome of elections in the next few years, it’s still difficult to know the ultimate outcome of the tax policy. Trump’s policies are unpredictable, and Biden’s policies after the election, should he win, might change considerably from what they have been once he doesn’t have to deal with reelection considerations.

So, we don’t know what taxes will look like in the future, but we do know what they are now, and they are low relative to most of the post-WWII era. At any rate, I don’t think anyone should count on lower taxes than we have right now, and my bias would be toward expecting higher taxes at some point in the future.

Because of these unknowns, I invest in a mix of different types of tax-sheltered or tax-deferred accounts. While this will vary from person to person, and especially country to country, my current order of importance in terms of where to put savings is Roth accounts get funded first because my family is still fairly young, middle-to-upper-middle income, and our tax rate might be higher in 15 or 20 years, so being able to tap this account tax-free might be useful. Also, there are annual limits on how much one can contribute to a Roth, so it’s best to steadily fund it over time.

Second, I fund what, I think, is the most underutilized account, our Health Savings Account, or HSA. This account isn’t taxed when money goes in or goes out, and I can control the investments within it. HSAs are extremely useful as long as one qualifies for them, and in the U.S., medical bills are costly, so the money will almost certainly get used at some point. Again, there are annual limits, so it makes sense to prioritize this annually as early as one can.

Next, I have a taxable account where I put money that I expect to spend on a significant expense, like a car or house repairs. This money is fully taxed, but is free from restrictions that tax-sheltered accounts might have.

And lastly, is a 401k if there is any money left. This has the most restrictions, and fewest investment options.

Having a broad combination of different accounts should give us the most flexibility in the future to adjust for any changes in tax policy or changes to our income. I think given that tax policy has a very high probability of changing over the next 10–20 years, flexibility is critical.

Political Risk #3: Geopolitics & The Warm War

The last, and biggest risk that ran through much of what we see Buffett doing lately is geopolitical risk, especially with China. When Buffett was asked directly about investing in Hong Kong and China, he said most of his investments would be in the U.S. because he understands the risks, strengths, and weaknesses of the U.S. much better than those of other countries. I think this is where we see a lot of self-constraint on Buffett’s part.

Here is my take after careful observation.

Charlie Munger had always admired China and the potential investment opportunities there more than Warren did. After making a successful investment in BYD Company (OTCPK:BYDDF) early on, Charlie’s China thesis looked like it would play out well. However, all of this changed after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in early 2022. Charlie’s big investment in Alibaba (BABA) lost a lot of money, and he admitted in an interview with CNBC’s Becky Quick before he died last year that it was a big mistake. Starting around August 2022, Berkshire began the process of selling its BYD position and has continued to do so.

Berkshire also sold a Taiwan Semiconductor (TSM) position in late 2022 which had only been recently purchased, and Buffett redeployed that capital to Japan instead. Now, Buffett is reducing Berkshire’s stake in Apple, which is a company that has massive exposure to China, both for manufacturing and sales.

This chain of events should spell out the overall danger Buffett thinks there is with geopolitics right now, particularly with China and Russia. However, the evidence doesn’t end there. Soon after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Buffett began adding to Berkshire’s stake in Occidental Petroleum (OXY) and has continued to do so ever since. Buffett also added significantly to Chevron (CVX) shares in 2022.

When we zoom out, the big picture view is fairly easy to see. First, Buffett is more than willing to invest outside the U.S., as we see with his addition to Berkshire’s Japanese trading company positions. Buffett even visited Japan. However, the Russian war in Ukraine, and China’s tacit support of the war, along with increased conflict in the Middle East, probably caused Buffett to protect Berkshire from a potential energy price spike like we experienced in the 1970s by buying OXY and Chevron stock, while continuously reducing both Berkshire’s direct and indirect exposure to China.

Additionally, Berkshire continues to build and hold record amounts of cash. I think it’s fair to say that Buffett thinks Berkshire’s single biggest risk is the change we’ve seen in geopolitics, particularly since the start of 2022.

What this could mean for investors

For investors who are seeking “all-weather” types of investments, or who expect Berkshire to be an all-weather investment, the adjustments Buffett has been making to address geopolitical risks should please them. My view is that virtually every single major geopolitical development over the past 4 years has been structurally inflationary. First, we had the pandemic, which indeed produced inflation, but it was quickly followed by two hot wars in Ukraine and Israel, and tariffs and sanctions have only increased since the pandemic. I would classify the current situation between Western democracies, led by the U.S., and those on the other side of the current hot wars, as a “Warm War,” where battles are being waged in various locations, but confrontation of superpowers has yet to occur. This Warm War has constrained and started to reverse the very open global neoliberal trade regime that’s been in place for the past 30 years. The clearest macro risk economically is inflation.

The only thing other than world peace that, I think, could reverse inflation is a recession. At this point, it should be obvious to any reasonable observer that the Federal Reserve isn’t targeting 2% inflation anymore.

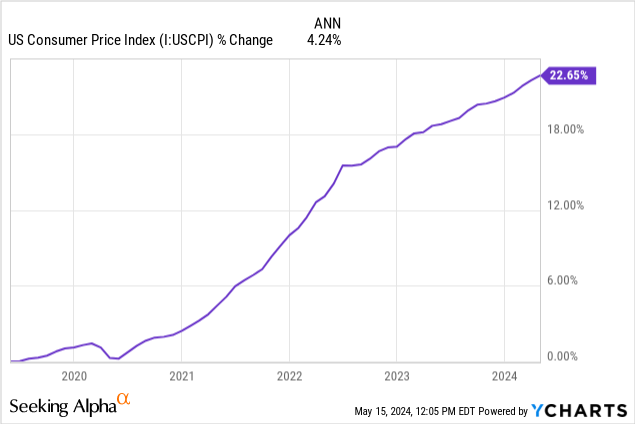

Over the past 5 years, U.S. CPI has averaged 4.24%, even if inflation fell to 2% by the start of 2025 (which is not guaranteed), and was held at that level successfully for an additional 5 years, inflation would average roughly 3% over that decade and not 2%. Personally, I think for the decade of 2020-2030, 4% average inflation is more likely than 2%. I think Buffett is very aware of this.

This has important implications for investors.

What I’m doing

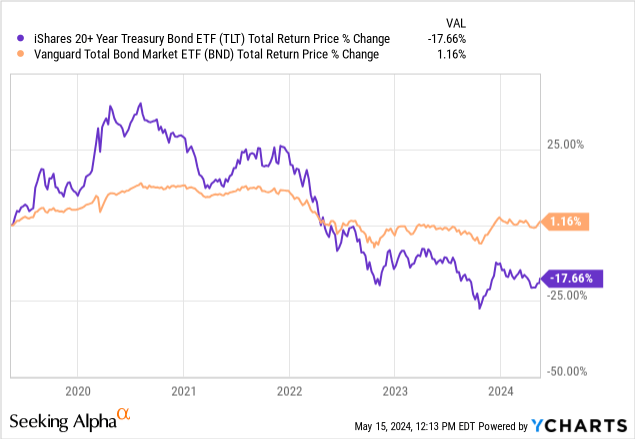

If investors haven’t done so, yet, they should think hard about how 4% inflation would affect the real returns on their portfolios during the rest of this decade. The first and easiest takeaway is that long-term government bonds remain overvalued and are the surest way to earn poor returns.

These returns are on top of the 22% loss of purchasing power. They could very well continue to be this poor. Buffett does not have significant exposure to long-term government bonds. Instead, he buys short-duration treasuries. The reason for that is they have a yield that is higher than inflation, and they don’t have risk of capital loss. Unless the Fed really messes up and lowers short-term rates while inflation stays high, these treasuries make a real return on top of being safe.

Personally, I own plenty of iShares Treasury Floating Rate Bond ETF (TFLO) (about 1/3 of my portfolio) likely for the same reason Buffett buys treasuries. It yields 5.3% and doesn’t have significant risk. I can sell it with the touch of a button and buy stocks if they get cheap enough, so it’s also very liquid. This protects against both inflation and a bear market. (It won’t protect against FOMO, though, if you are benchmarking to an index that is 100% stocks, so you need to know your return goals.)

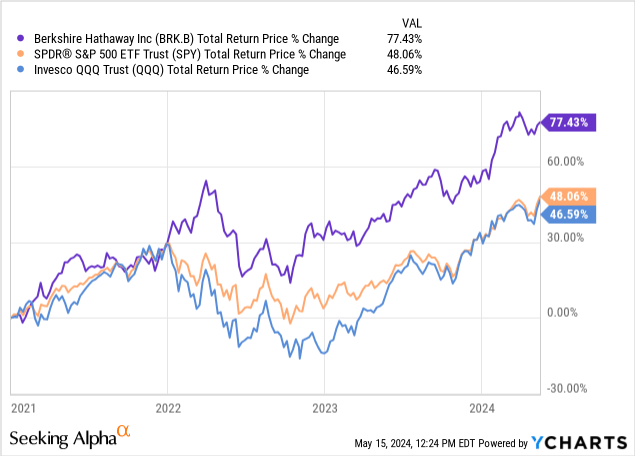

The other 2/3rds of my portfolio is invested in the stock of high-quality businesses. I define “high quality” as the ability to grow earnings faster than inflation. This means that my portfolio, which I consider an “all-weather” portfolio, is fully prepared for a higher inflation world, and also for the potential of a bear market. I believe Berkshire is positioned the same way. We entered this higher inflationary world around 2021, but then it became more structural due to geopolitics in 2022. Below are Berkshire’s returns since then compared to the S&P 500 (SPY) and (QQQ).

Conclusion

All-in-all, I thought the 2024 annual meeting was one of the more downbeat meetings I’ve seen. My biggest takeaway is that political risk is something all investors should be thinking about. While I feel I have adequate cash and have made several adjustments to my investments, like selling and avoiding Chinese stocks and businesses with large Chinese exposure, adding positions like Occidental Petroleum and Devon Energy (DVN) to help mitigate an oil price spike, reducing holdings that have above-average debt and low earnings growth, I’m still probably not finished adjusting to the new Warm War environment. I also haven’t made any significant adjustments based on internal U.S. political risk — yet. Those adjustments, if I make any, likely won’t come until Q4 when the election is closer in view.

Since the start of 2023, I’ve essentially been practicing a barbell strategy, with cash on one end and high-quality growth at the other (not all that different from Berkshire’s approach). I don’t see any reason to deviate much from the overall strategy. If anything, Berkshire’s annual meeting solidified the idea that the two best ways to mitigate the current higher inflation environment are higher-yielding cash/treasuries and businesses that can either pass the inflation on to customers or grow their businesses at a faster rate. I expect the remainder of this decade will be as much about avoiding losing too much to inflation or losing due to changing global politics as it will getting the types of returns investors have become accustomed to during the past 15 years.

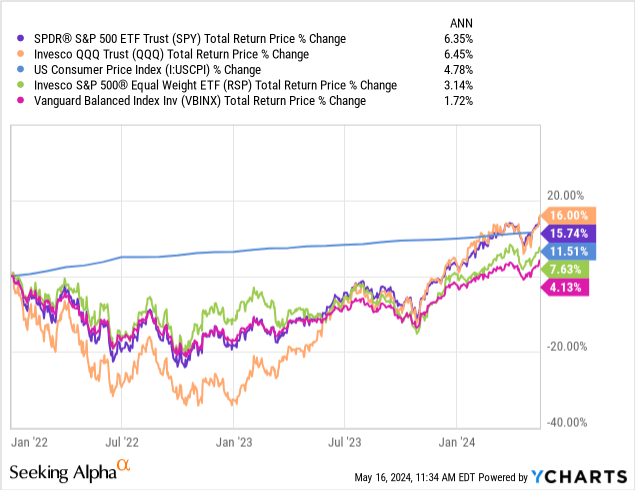

While indices are making new highs this week, both SPY and QQQ have barely posted positive real returns since 2022. The equal-weighted S&P 500 Index ETF (RSP) is negative in real terms, and Vanguard’s 60/40 fund (VBINX) remains underwater in real terms after nearly 2.5 years. Inflation makes it feel like investments have been performing well the past couple of years, but they haven’t. Not understanding this is likely the biggest mistake most investors will make this decade.

I think carefully studying Buffett and Berkshire can provide some clues on how to avoid a lost decade of investments. Or, simply owning an overweight position in Berkshire stock as I do will likely help as well.

Read the full article here

Leave a Reply