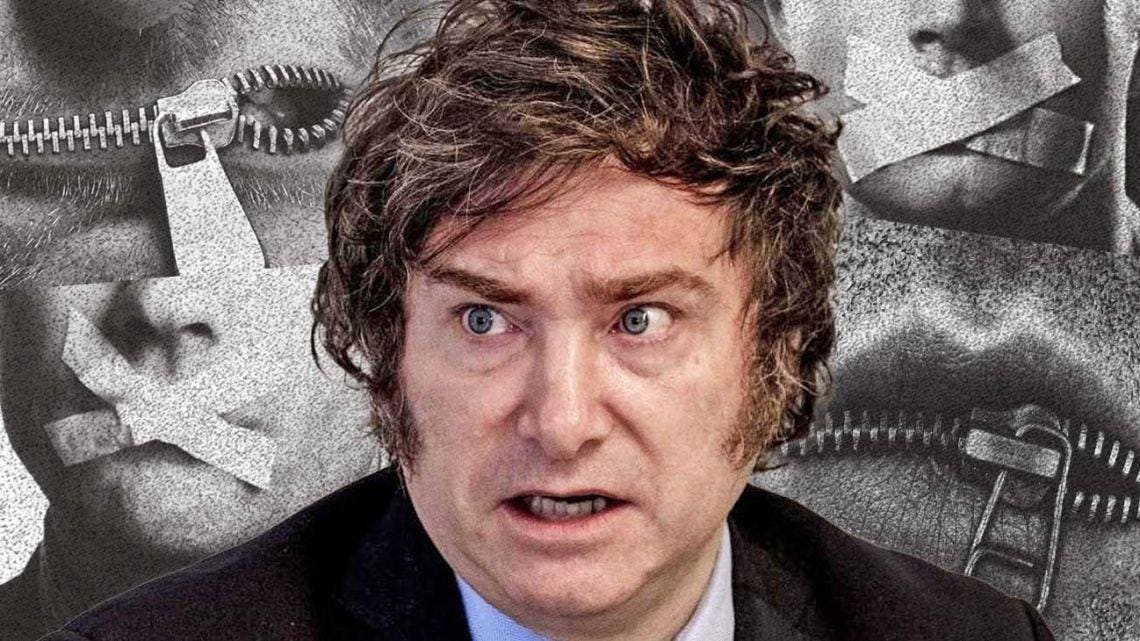

The business sector is traditionally risk averse in political terms. Over the last several weeks, Argentina’s “suits” have been forced to reckon with a situation of increased uncertainty amidst their incredulity at Juntos por el Cambio’s electoral performance, especially Buenos Aires City Mayor Horacio Rodríguez Larreta, their favorite. For many of them even the pan-Peronist coalition candidate, Economy Minister Sergio Massa, represented a sort of “rational” continuity with which they could cope with. Instead, they got the “Black Swan” scenario of Javier Milei, the ultra-libertarian economist who promises to burn the Central Bank and overhaul the state and whose vice-presidential candidate comes as close to denying the human rights violations of the last military dictatorship as anyone aspiring to the Presidency of the Senate could be.

Nothing farther from political correctness appears possible within the Argentine political ecosystem, fuelling the panic of the “círculo rojo” (or group of influential decision makers with real firepower). What they are all thinking, but are not willing to say publicly, is that they believe a Milei administration would be marked by a level of institutional instability so great that it would quickly lead to a situation of social unrest. Paralyzed by their fear and lack of comprehension of the “Milei phenomenon,” they look forward with a sense of inevitability to a hectic 2024 when the macroeconomic variables are expected to go haywire to the tune of the libertarian economist’s utopian agenda that includes his “chainsaw plan” to hack 13 percentage points off public expenditure and the intention of dollarizing the economy, among others. It is unclear how long Milei and his associates would last in the Casa Rosada, they suggest. While they can’t really say this out loud, they look at the other electoral contenders, especially Patricia Bullrich, as incapable of putting a dent on Milei’s lead

While we are still a long way from the general election, and a potential run-off, Milei has managed to instil a sense of impending victory that his rivals haven’t been able to challenge. Since the PASO primaries, he’s flooded the media, taking his victory lap across friendly TV shows and then sending his emissaries to explain their coalition’s policy plans. His economic advisers were grilled on live television regarding the feasibility of the plan to dollarize the economy and whether they would cut ties with “communists” like China, despite their importance in Argentina’s trade balance. They weren’t too solid, or consistent with each other, but that didn’t matter. Vice-presidential candidate Victoria Villaruel was put under the spotlight as her revisionist vision of the political violence of the 1970s and 1980s. They even put on a show at the City legislature that led to confrontations with human rights groups. It didn’t make a difference. Diana Mondino, who is expected to head the Foreign Ministry in a Milei-Villaruel administration, was questioned for telling a British media outlet that Argentina would soften its stance on the Malvinas (Falkland) Islands by “respecting the rights” of the Kelpers. As Milei and his team challenged some of the “pillars” of Argentine mainstream socio-political thought, his apparent popularity and voting intention remained as solid as ever.

Going back to the beginning, there are two factors at play when analyzing what a Milei administration will actually look like. First is the so-called “Baglini theorem” named after the late Unión Cívica Radical (UCR) politician Raúl Baglini, who suggested that ideas and proposals become less extreme as leaders or political groups get closer to taking office and having real power. Conversely, a candidate with low chances of winning can make extravagant proposals and move toward the edges of the ideological spectrum, but will be forced to adopt more mainstream positions if he were to win. A second issue has to do with La Libertad Avanza, Milei’s libertarian party, and their capacity to effectively run the state. According to the latest report by the official INDEC national statistics bureau, the “centralized administration” of the national state had 55,000 employees in May. That includes every Ministry, the office of the Cabinet Chief, and the Presidency. There’s another 136,000 employees in the “decentralized” part of the state which includes major agencies, regulatory entities and government services. And finally another 40,000 distributed among other state structures. Do Milei and LLA have enough people to populate the top posts of public administration? And if they did, while trying to put their ambitious reform package in place, would they moderate their ambitions and try to run the state within the bounds of its rules — and the law — or will they radicalize their stance and potentially face-off with the other branches of the state?

Those issues are tied to what is probably Milei’s most powerful political weapon: the concept of the “caste” that lives off the state and is supposedly responsible for Argentina’s current state of decrepitude. It is no secret that Milei’s top lieutenants are absolutely polluted by members of the “caste.” He’s signed up provincial leaders that are pure examples of the “caste” throughout the campaign and has been having meetings with union leaders lately, namely restaurant-workers’ union boss Luis Barrionuevo, who can hardly be considered an outsider. If Milei and his team had any plans to effectively populate and run the state’s apparatus, they will most definitely have to rely on people that belong to the “caste,” even if he aggressively reduces its size. Fortunately for him, it doesn’t matter to his voters, who seem willing to allow Milei and LLA to do whatever they want, given they represent “something different.” His opponents are terrified at being catalogued as part of the caste, an allegation that Bullrich and Massa cannot protect themselves against. Being identified as a member of the caste quickly leads to digital harassment that seeks to cancel and discredit the victim, weighing heavily against anyone who wishes to challenge Milei.

It is difficult not to agree with the libertarian lawmaker and his followers that there is something inherently wrong with the state of things and that, in some way, the same people have always been in charge. Since the return of democracy in 1983, either Peronists, Radicals or Mauricio Macri’s anti-Peronists have been in charge. Many of the politicians on both sides of the aisle have had public posts since 1983 or have been involved with several administrations, most of which have failed at improving general welfare. According to political analyst Artemio López, a decrease in the levels of industrialization is visible at least since 2012, which has led to a fall in the share of workers’ earnings as a percentage of GDP, which was absorbed by private-sector gains. This loss of purchasing power, together with a feeling of betrayal at the hands of the leading coalitions, is fertile breeding ground for the emergence of an outsider that promises to revolutionize the system. Extrapolating from López’s domestic vision, the hegemonic political-economic model of the post-War XX century has run out of steam, generating more inequality and less upward social mobility throughout the Western world. Milei, and other far-right populists, appear to capture this discontent as they promise to upend the status quo, which is the real reason they are popular, not their underlying policy orientation.

With two debates ahead of us before the general election, the ultra-libertarian economist holds the lead while Massa is trying to position himself as the runner-up who would make it to the run-off. Bullrich, according to the latest figures, is a bit further behind in the race. Massa’s response has been to announce distributive policies that supposedly please the core Peronist voter, and probably mark a final break with the International Monetary Fund. Bullrich has brought economist Carlos Melconian onboard to confront with Milei’s ideas. It feels insufficient if they aspire to stop the libertarian wave.

This piece was originally published in the Buenos Aires Times, Argentina’s only English-language newspaper.

Read the full article here

Leave a Reply