The “Big Number” (the Consumer Price Index) is out, and once again the major media channels are full of misinformation.

- “September Inflation Shows Price Pressures Persist” – WSJ Headline (Oct 12, 2023)

- “The path to fully wrangling inflation remains long and bumpy.” – NY Times (Oct 12, 2023)

- “US Consumer Prices Rise at Brisk Pace for Second Straight Month.” – Bloomberg (Oct 12, 2023)

- “Prices rose 3.7 percent in September as Fed keeps up inflation fight. Officials still have more work to do to tame consumer prices.” The Washington Post (Oct 12, 2023)

- “Treasury yields rise as elevated inflation keeps Fed rate rise in play.” – Financial Times (Oct 12, 2023)

In fact, inflation has already been brought under control – though you wouldn’t know it from the headlines.

The Monthly CPI Panic

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) released by the Bureau of Labor Statistics is the biggest event of the month for inflationistas. Within minutes of the 8:30 am press release, the “breaking news” bulletins are up online, and reporters start ringing up “experts” for colorful soundbites. The resulting narrative is superficial and, frankly, un-insightful, but with a decisive bias towards pessimism. The default “take” seems to be that, no matter what the numbers show exactly, inflation is still a danger. It is still “untamed” – and the Fed therefore needs to reman stern and vigilant, and keep its foot on the pedal to drive interest rates even higher, or at least maintain them “higher for longer.” The markets swoon, predictably. This happens almost every month, at least for the last year and a half, like some recurring tropical fever.

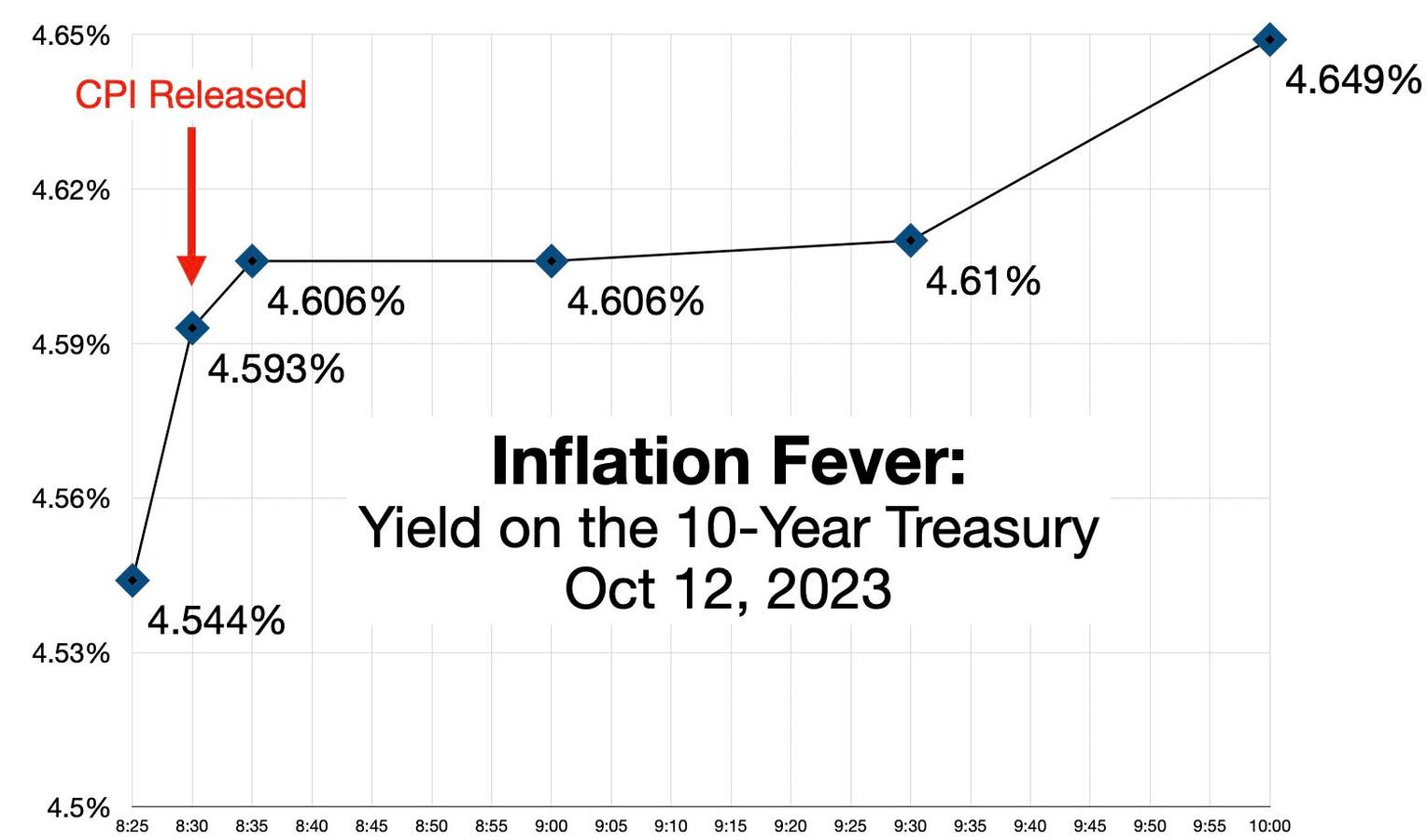

Consider the figures out yesterday (Oct 12). The CPI tells us that prices rose 3.7% year over year, which is of course still well above the 2% target set by the Federal Reserve. The Treasury bond markets, set on a hair-trigger, responded by shedding something like half a trillion dollars in value. Yields on the 10-year Treasury jumped 2.3% from 8:25 am to 10:00 am, and closed up 3.5% for the day – the 4th largest one-day move in a year.

But the CPI is known – well-known! – to be essentially a false signal. To get a better picture of what is really happening, the CPI headline figure needs to be qualified and adjusted in several ways, to get closer to a true and accurate understanding of the current price trends in the economy.

The easiest adjustments are:

- Compare the CPI with the Federal Reserve’s preferred metric, the PCE (Personal Consumption Expenditure Index)

- Compare the Headine CPI with the Reduced Volatility Versions of the PCE

Step 1: Switch to the Fed’s Preferred Inflation Measure, The PCE

There are many things wrong with our current methods of measuring inflation – starting with the obvious fact that there are far too many measures, which produce figures of vary over a very large range (2 to 1 typically). The CPI is so deeply flawed that the Federal Reserve decided decades ago to ignore it for purposes of calibrating monetary policy. The Fed relies instead on a measure called the Personal Consumption Expenditures Index (PCE), which is widely regarded as a superior (though still imperfect) metric. But the media have not followed the Fed’s example. The monthly CPI is still treated as the most important inflation metric by most of the leading media channels. It is still the “headline” number – and as such, it continues to play an outsized role in forming public opinion about inflation.

Comparing the two measures shows that the CPI almost always runs “hot” – exaggerating the apparent threat of inflation. This distortion has become more pronounced since January 2022, when the Federal Reserve began its aggressive program of interest rate increases. The PCE has been running more than 1 full percentage point lower than the CPI.

Step 2: Volatility Reducing Adjustments

It is also generally agreed that the volatility in the inflation signal should be reduced to get an accurate picture of the broad price trends in the economy. There are many ways to attack this, and the Federal Reserve system has spawned at least half a dozen alternative volatility-reducing metrics.

Two ways in which this is accomplished are:

- the elimination of Food and Energy components from the calculation, i.e., the Core PCE

- the trimming of the components making up the upper and lower “tails” of the PCE “basket” – i.e., those components which increased the most and those which decreased the most, resulting in the Trimmed Mean PCE (published by the Dallas Federal Reserve)

The gap between the unadjusted CPI and the inflation metrics that employ volatility-reduction techniques is larger still. The headline number ranges up to 250 basis points above the adjusted figures.

Over the last 20 months, the Core PCE has averaged 0.8% lower than the CPI, and the Dallas Fed’s Trimmed Mean measure averaged 1.25% lower. (All these are year-over-year measures – I’ll comment further on that point below.)

The “Adjusted” CPI

There is actually no such thing as the Adjusted CPI, officially speaking. But since the September CPI is the most current measure we have at this time (the PCE is issued by the Bureau of Economic Analysis, part of the Department of Commerce, and will not come out for another 2 weeks – by which point it will seem, in the eyes of the press, to be semi-old news), we can use the information described above to get some idea of what to expect.

Assuming that the average discrepancies will hold, we might expect that the PCE will come in ½% to 1% lower than the CPI. And the Core PCE and Trimmed Mean PCE will be even lower. Overall, it is reasonable to mark down the year-over-year CPI from 3.7% to around 2.7% or so, as the more likely level of “true” inflation (on a year over year basis).

The 3-Month Run Rate

But the year-over-year calculation is itself flawed.

The next adjustment is to shorten the averaging interval from 12 months (the year-over-year measure that the headline CPI uses) to a shorter interval that gives a more accurate picture of the current run-rate of inflation. The 3-month annualized run rate seems to be emerging as the better way to calculate the current inflation rate. (The arguments for this are laid out in detail in the previous column, here.)

The Core PCE, on a 3-month annualized run rate, comes in a full 2% lower than the headline CPI.

Summary

These are rough adjustments, admittedly. The difficulties of measuring inflation, and of comparing different ways of measuring it, are complex. But as an antidote to the inflation panic that the CPI generally induces, these adjustments show that the true picture today is much less alarming that the headline figure. The level of price inflation is likely 1% to 2% lower than the CPI number, which would bring it well in line with the Federal Reserve’s 2% target.

Hopefully, the authorities see this similarly, and the Fed will not tumble forward into a new round of rate increases, which would inflict significant collateral damage on the economy (another subject for a forthcoming column).

For more on this topic, see also:

Read the full article here

Leave a Reply