Javier Milei’s surprise victory in Argentina’s presidential PASO primary shocked the world. Not just the domestic political ecosystem was stunned – a global reaction saw Milei’s digital popularity overtake Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin in the immediate aftermath of the election. The ultra-libertarian economist with wild hair is such a sensation that even an investor report by JPMorgan Chase

JPM

Very quickly, Milei has become “larger than life.” His contenders meanwhile remain paralyzed, going on a media frenzy that has dominated the airwaves. It is solidifying a sort of self-fulfilling prophecy, by which a frontrunner in a hotly contested race – with the leading political coalitions separated by mere percentage points – is already being perceived as the next president. His eccentric nature and the novelty of his unexpected victory, especially given the lack of a nationwide political organization behind him, have left Argentina’s intelligentsia dumbfounded, scratching their heads to understand a phenomenon that is absolutely alien to them. They are fearful and, along with certain antagonistic political sectors, envision an apocalyptic future when only recently there seemed to be an optimistic outlook for the country regardless of whether Juntos por el Cambio or Unión por la Patria won the election.

There are, in my opinion, four clear misconceptions about Milei that must be addressed in order to understand the phenomenon.

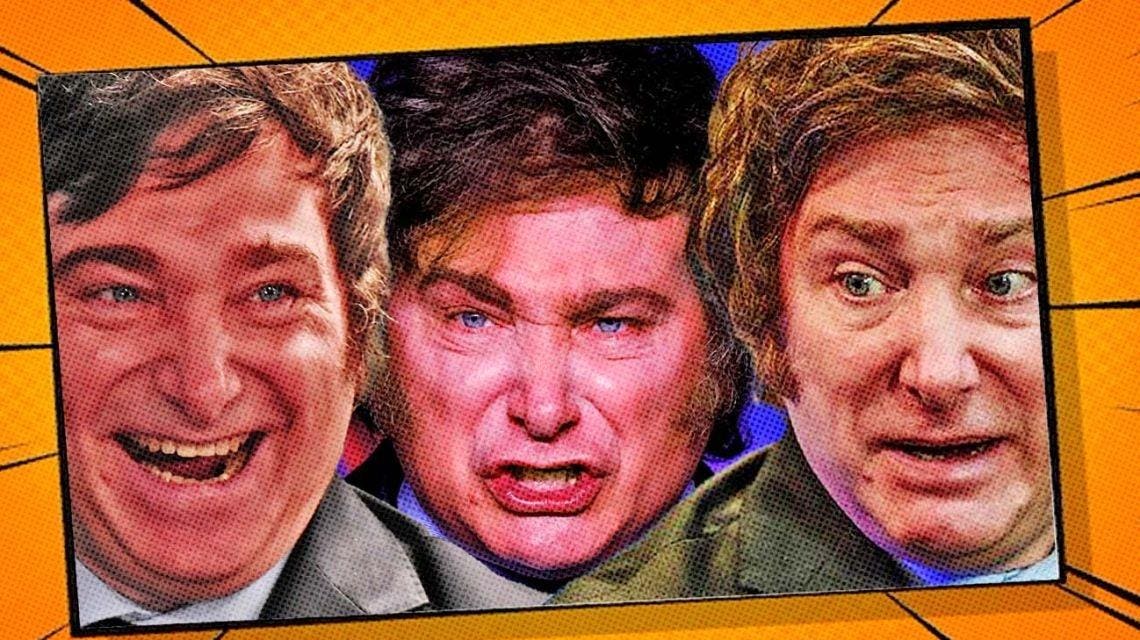

First and foremost, Argentina’s socio-political mainstream lacks the sociological and cognitive frameworks to understand Milei, leading them to chastise him – to his electoral benefit. There is no doubt that the ultra-libertarian economist is a weird character. His unkempt hairdo and aggressively expressive mannerisms clash with the standard view of what a political leader should look and act like. His impulsiveness and loud tone in televised debates stray from the norm which favors moderation and good manners. Milei speaks to his dogs, both living and dead, and is convinced he has somehow been chosen by “The One” to lead Argentina out of decrepitude. His political rallies are part heavy-metal concert and part evangelical mass, where grassroots followers are spellbound by the leader that will finally bury the political “caste” that has for years perpetuated this state of chronic malaise.

Thus, he manages to break away from the worldview held by the Buenos Aires elites. Milei is a media sensation – he has consolidated his position on television panels where he aggressively debates unprepared pundits, dogmatically arguing with Austrian economic theory, generating clips that go wildly viral on social media. For those who are disillusioned with the system and are constantly browsing social media on their phone, Milei and his version of what reality should look like, especially from a macroeconomic standpoint, has become a revealed truth.

While Patricia Bullrich, Horacio Rodríguez Larreta, and Sergio Massa concentrated their digital presence in Argentina’s central region, Milei was a nationwide phenomenon, according to a report put together by social media expert Diego Corbalan, which saw the libertarian absorbing some 29 percent of the digital conversation ahead of the election, compared to 23 percent for Massa, 21 percent for Bullrich and 15 percent for Rodríguez Larreta. This national digital reach was later replicated electorally. Milei appears as an expression of anti-system sentiment that connects with the populist message of “draining the swamp” that proved to be so effective for Donald Trump in the United States. According to political data analysts Antonio Milanese and Juani Belbis, Milei’s average voter is consistent throughout income level, age, and former political affiliation.

Unable to understand the character before them, Argentina’s intelligentsia has therefore decided that “he’s crazy.” And because he’s a nut job, he’s completely unpredictable and this inevitably will lead to another massive social crisis that will see Argentina in flames once again. As highlighted above, there are many reasons to consider Milei an oddball. Especially striking are his telepathic connections with his dogs, being a self-proclaimed tantric sex coach, and his virulent temper. It is difficult to envision how a person with this personality will be able to form a coherent cabinet, draft a reasonable government platform and put it into place by negotiation with other political spaces.

Yet these features shouldn’t make him any “crazier” than the rest of the political class, or society for that matter. Whether he comes up with his decisions based on conversations with dead economists through his dogs, belief in God, spirituality or ideology, if he were to win he would have to govern within the realms of Argentine institutions, meaning there will be pretty clear swimlanes demarking the boundaries. Ultimately, Argentina has seen both messianic characters and formed technocrats “crash the boat” so there’s no reason to assume Milei is more or less likely given his eccentricities.

Another interesting characteristic regarding how Milei is being understood is that many are acting as if he’s already won the election. In the immediate aftermath of the PASO primaries, Javier Milei became the center of the media solar system. Every news site and TV channel was obsessed with him, as was the audience (if measured by ratings and web-traffic figures). Social media interactions went through the roof. Web search volume for Milei was more than 10 times higher than that for Massa and Bullrich in the days after the PASO primaries and still remains well above, even generating large digital audiences across the globe with a large impact in countries including Italy, Chile, Spain, the United States, and even Iceland, according to Corbalán’s analysis.

Analysts and pundits are closely scrutinizing his governing platform and public statements, trying to anticipate who will be in his cabinet and how society and the economy will react once he’s in office. Supporters are already imagining a libertarian utopia while antagonistic sectors are suggesting an anti-right wing coalition is necessary to oppose him. The private sector is terrified, trying to understand how they will run their businesses in a world of unpredictability and incoherence. It feels as if most actors are projecting their expectations of what a Milei Presidency will look like as a reality that is already occurring.

All of which ultimately is creating a feedback loop that is virtuous for Milei and vicious for his political opponents, especially Bullrich and Juntos por el Cambio. While Massa is trying to build a narrative on the back of his tenure as “war general” at the Economy Ministry, battling the evil International Monetary Fund while trying to safeguard society’s hard-won rights, Bullrich remains paralyzed. Juntos por el Cambio hasn’t been able to react, ceding the spotlight to Milei who is eating their lunch. The debate about whether to move to the center or toughen their stance to dispute the hardline vote with Milei smells awfully similar to the disastrous campaign strategy for the primaries, with Rodríguez Larreta and Bullrich seemingly more worried about political allegiances and appointments than generating empathy with the electorate.

The combination of these four factors is progressively solidifying Milei’s position as the frontrunner. The fact that he is “not like them,” the usual politicians and businessmen, and that he’s “crazy” make him extremely attractive from a media standpoint, and electorally too. In the age of near total smartphone and Internet penetration, Milei has proven that a viral phenomenon is more powerful than the traditional party structures that supposedly guarantee the vote throughout the nation. Nothing could show this more clearly than Rodríguez Larreta’s failed bid for the Presidency, with the once-frontrunner earning just over 11 percent of the vote in the primaries.

We’re still “a long way” from the general election, scheduled for October 22, and the expected run-off, to be held on November 19. Unless the main coalitions wake up, Milei could be on his way to the Casa Rosada.

This piece was originally published in the Buenos Aires Times, Argentina’s only English-language newspaper.

Read the full article here

Leave a Reply