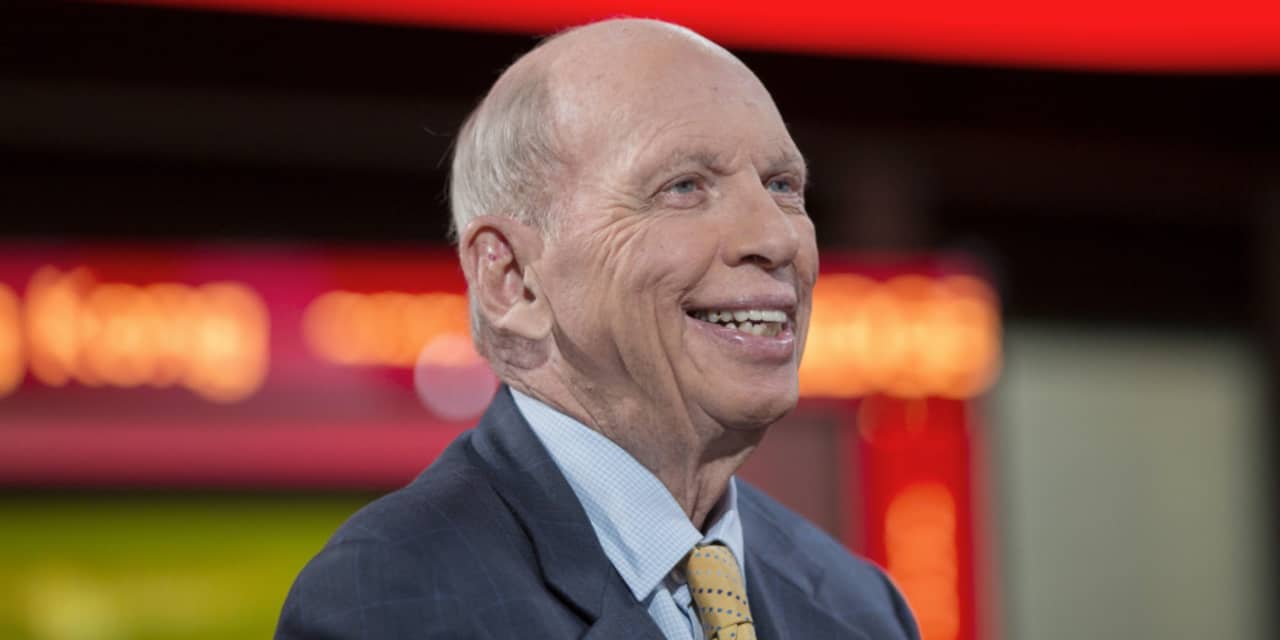

Byron Wien, who provided insights on the economy, financial markets and global affairs for 38 years as a Wall Street strategist most recently at Blackstone, died Wednesday at 90.

Wien was most famous for his annual list of 10 surprises—a series of unexpected financial events that he thought could unfold in the coming year—and for a list of 20 life lessons that included the importance of reading, travel, sleep, and never retiring.

Wien followed his final bit of advice and continued to work at Blackstone until his death.

A hip injury limited his mobility in recent years and crimped what had been a punishing travel schedule but he used Zoom calls to his advantage. Wien was the oldest Blackstone employee, with the next youngest being CEO Steve Schwarzman, 76. Wien worked at Blackstone for 14 years, most recently as vice chairman of private wealth solutions.

Wien was on the job as recently as last week, participating in firmwide calls during which he offered his take on markets and global affairs.

Barron’s wrote about Wien periodically over the past 25 years and did a cover story on him in 2016. In that article, Loews CEO Jim Tisch said: “Byron is an 83-year-old man chronologically, but in temperament, he is 45. His passion is the markets and the world around him, and that comes shining through anytime you talk to him. He’s well connected and well-informed and is always looking to gain new insights.”

Wien was engaging and a great raconteur who was popular with financial advisors who Blackstone courted to sell the firm’s retail-oriented products like Blackstone Real Estate Income Trust.

His speaking skills were evident at a meeting of

UBS

financial advisors at the 21 Club in Manhattan that this reporter attended while preparing a cover story on Wien in 2016.

After a florid introduction in which the host likened him to such greats as Jim Thorpe, Vince Lombardi, Michael Jordan, and even Socrates, Wien said, “I sure wish my first wife could have heard that.”

At the 21 Club meeting, he went through his life lessons, emphasizing some career advice: “Don’t try to be better than your competitors; try to be different.” He also said that while many focus on the importance of diet and exercise, he felt that sufficient sleep is underappreciated. “Sleep is the fuel of performance.”

While he had an apartment on Park Avenue and a summer home in Wainscott (part of East Hampton on Long Island), he lived modestly given his wealth, reflecting his Depression-era upbringing.

This reporter got to know Wien over more than 25 years and after meeting for lunch, Wien regularly asked for a doggie bag. When he left a doggie bag in his fridge at his Manhattan office one summer Friday, he had a friend stop by and bring it out to him in Wainscott so the food wouldn’t go to waste.

Wien didn’t fly private, preferring commercial flights and he counseled his superrich friends that it was a bad idea to let their children fly private because he thought it changed them for the worse, separated them from peers and created a sense of entitlement.

He was a lively writer and caused a stir two decades ago when he presciently warned of potential economic stagnation in Europe, writing that the continent was in danger of becoming a “vast open-air museum.”

Wien loved to network and be around powerful and influential people from Wall Street, industry, and government,

Reflecting his clout and charm, Wien orchestrated a series of lunches in the Hamptons each summer that brought together leading investors and other notables to discuss the markets, economy, politics and the world. Participants over the years included Bill Ackman, Carl Icahn, George Soros and David Koch. He would ask every participant to speak about his or her views.

Wien regularly wrote essays summing up sentiment at the lunches while noting that the consensus view sometimes ended up being a contrarian indicator.

Wien was most famous for his 10 surprises, a collection of predictions that he made at the start of each of the past 38 years. His view was that Wall Street figured the odds of each were maybe one in three and he viewed the probability of each was higher.

His surprises had a good record although they look mixed so far in 2023. Collaborating with Joe Zidle, the other Blackstone strategist, Wien was correct in predicting a strong dollar and that the Federal Reserve would stay tighter for longer this year but wrong on strength in the Chinese economy and a cease-fire in the Russia/Ukraine war. Part of the reason for the surprises list was to provoke investors and get them to consider the unexpected.

Wien made his reputation as a strategist at

Morgan Stanley

in the late 1980s and 1990s. He told Barron’s that when he wanted to originate the Surprises list as at Morgan Stanley in 1985, the firm initially nixed the idea.

“They said, ‘Byron, you could get all 10 wrong and you would embarrass the firm and humiliate yourself. Frankly, we don’t give a damn about your humiliation, but we don’t want the firm to be embarrassed.’ ” Wien told Barron’s for our 2016 profile.

Under pressure from Wien, the firm relented, and the 10 Surprises became so popular that Morgan Stanley took a service mark on the phrase, which it licensed to Wien each year for $1.

Wien also is known for his Life Lessons. He came up with that idea at a 2013 conference in Vail, Colo., when he was asked by the host to scrap his usual financial talk and offer a more personal presentation. Initially annoyed at having to shift gears, Wien quickly came up with 12 ideas, which he then expanded to 20.

One of his Life Lessons involves philanthropy and his views differed from other wealthy people. “Try to relieve pain rather than spread joy. Music, theater, and art museums have many affluent supporters, give the best parties, and can add to your social luster in the community. They don’t need you. Social service, hospital, and educational institutions can make the world a better place and help the disadvantaged make their way toward the American dream,” Wien told Barron’s.

Reflecting his philosophy, Wien endowed two professorships at Harvard University, his alma mater, as well as made gifts supporting Harvard’s financial aid, including a scholarship for orphans.

Wien, who was orphaned at 14, excelled in high school and got a lucky break when a Harvard admissions representative came to his Chicago school and asked the guidance counselor to recommend a single student for an interview with an admissions dean. Harvard was seeking what then amounted to diversity—more public school students to balance those from prep schools like Andover, Exeter and Groton.

“The guidance counselor called me in and said, ‘Wien—they called you by your last name then—you’re our pick. Go downtown and don’t make a fool of yourself.’ That changed my life,” Wien said.

|In our 2016 profile, He noted some regrets, including not having children. He had a close relationship with his godchildren. And he shared many interests—reading, theater, sailing—with his second wife of more than 40 years, Anita Volz Wien. She’s chairman of the Observatory Group, an economic and political advisory firm.

Wien admired Henry Kissinger, now 100, because Kissinger remained active and influential even at the century mark. He hoped to continue working in his 90s.

Wien loved living in New York and wouldn’t move to Florida or another low-tax state like some of his wealthy friends.

“I might have a different attitude if I made a few billion dollars,” he told Barron’s in 2016. “I’ve made enough money; the taxes don’t hurt. It’s a privilege to live in New York. Besides the theater and culture, there are so many interesting people. That’s what life is about, exchanging ideas with interesting people.”

10 life lessons from Byron Wein

- Network intensely. Luck plays a big role in life, and there is no better way to increase your luck than by knowing as many people as possible. Nurture your network by sending articles, books and emails to people to show you’re thinking about them. Write op-eds and thought pieces for major publications. Organize discussion groups to bring your thoughtful friends together.

- When you meet someone new, treat that person as a friend. Assume he or she is a winner and will become a positive force in your life. Most people wait for others to prove their value. Give them the benefit of the doubt from the start. Occasionally you will be disappointed, but your network will broaden rapidly if you follow this path.

- Read all the time. Don’t just do it because you’re curious about something, read actively. Have a point of view before you start a book or article and see if what you think is confirmed or refuted by the author. If you do that, you will read faster and comprehend more.

- Get enough sleep. Seven hours will do until you’re 60, eight from 60 to 70, nine thereafter, which might include eight hours at night and a one-hour afternoon nap.

- Travel extensively. Try to get everywhere before you wear out. Attempt to meet local interesting people where you travel and keep in contact with them throughout your life. See them when you return to a place.

- On philanthropy, try to relieve pain rather than spread joy. Music, theater and art museums have many affluent supporters, give the best parties and can add to your social luster in a community. They don’t need you. Social service, hospitals and educational institutions can make the world a better place and help the disadvantaged make their way toward the American dream.

- The hard way is always the right way. Never take shortcuts, except when driving home from the Hamptons. Shortcuts can be construed as sloppiness, a career killer.

- Don’t try to be better than your competitors, try to be different. There is always going to be someone smarter than you, but there may not be someone who is more imaginative.

- When seeking a career as you come out of school or making a job change, always take the job that looks like it will be the most enjoyable. If it pays the most, you’re lucky. If it doesn’t, take it anyway, I took a severe pay cut to accept each of the two best jobs I’ve ever had, and they both turned out to be exceptionally rewarding financially.

- Never retire. If you work forever, you can live forever. I know there is an abundance of biological evidence against this theory, but I’m going with it anyway.

Write to Andrew Bary at andrew.bary@barrons.com

Read the full article here

Leave a Reply