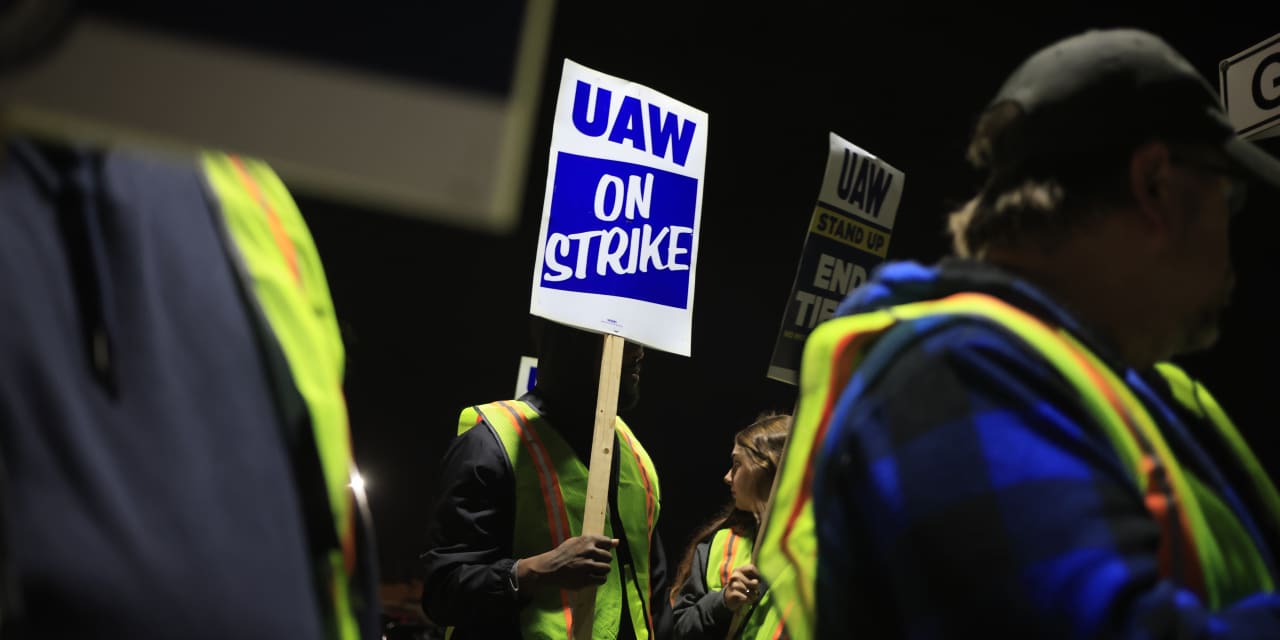

The 2023 United Auto Workers strike against the Detroit Three auto makers just turned 41 days old, beating the most recent big walkout, in 2019.

Details of what’s in the deal aren’t available. Ford and the UAW didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment.

A tentative agreement is a very big deal, but it doesn’t end the strike. This work stoppage has been different and several steps remain before investors can sound the all-clear.

The walkout has been no fun for anyone. Through midday trading Wednesday, shares of General Motors (GM) and

Ford Motor

(F) were down about 28% and 25%, respectively since the start of July, when labor issues started to weigh on investor sentiment. The

S&P 500

is down about 6% over the same span.

Shares of

Stellantis

(STLA), a more global company, are up about 7%.

Investors tend to avoid auto stocks during a strike. That puts downward pressure on prices and isn’t a surprise.

A big difference this time is inflation matters, a lot, while it didn’t matter as much when the union was negotiating with GM in 2019. The average annual wage increase in that agreement, ratified Oct. 25, 2019, after 40 days, was less than 2%. Inflation has averaged closer to 4% over the past four years, so workers lost ground in broad terms, even though there were other parts of the contract that affected take-home pay, including profit-sharing and changes to wage increases linked to seniority.

That’s a reason this negotiation has been so difficult.

Also different is that the UAW is striking against all three auto makers at once. In the past, the UAW picked one company to negotiate with and then took that agreement to the other two as a basis for talks.

Ford has a deal, but Ford workers will likely still be out until ratification, which isn’t a slam dunk. Mack Truck workers represented by the UAW voted down a tentative agreement that was presented to members by union leadership.

What’s more, a deal for Ford isn’t a deal for GM or Stellantis. Both have to come to their own tentative agreements and then have employees ratify a new contract.

Another reason this strike has been different is, frankly,

Tesla

(TSLA). Its rise as a significant nonunion competitor has the Detroit Three nervous. When GM workers ratified the 2019 contract, Tesla’s market capitalization was about $45 billion and GM’s was about $55 billion. Now, Tesla’s market capitalization is closer to $700 billion while GM’s is less than $40 billion.

And Tesla was delivering about 100,000 vehicles per quarter from one assembly plant, which it bought from GM. Now it is delivering about 450,000 per quarter from four plants spread around the world.

GM, Ford, and

Stellantis

(STLA) have reason to be worried about competing against Tesla and other EV start-ups while they seek to defend their market share against

Toyota Motor

(TM). That is a reason for them to hold the line and one reason that one agreement with an auto maker might not be adopted quickly by the other two.

The union, meanwhile, has been taking a hard line because it wants to see workers do better because people on the assembly line have already contributed significantly to helping the Detroit Three to consistently make money. The improvement in profitability is clear.

Over the past decade, GM and Ford, combined, have generated roughly $10.5 billion in operating profit a year, with a profit margin of 4%. In the 10 years leading into the 2008-2009 financial crisis, those numbers were about $3 billion a year, with a margin of 1%.

Barron’s excluded Stellantis from the calculations because the series of mergers that created it is complicated, making comparisons difficult, but the trends at Ford and GM generally apply to it.

Ford and GM lost a cumulative $100 billion between 2005 and 2009, which is why the companies asked for and received concessions from workers. Barron’s has estimated, using Federal Reserve data, that the ground ceded by the union has saved the Detroit Three about $2 billion a year on average since 2007.

Now the companies are offering wage increases in the range of 5% to 6% a year with more enhancements to wage progression and retirement benefits. So far, the UAW hasn’t blinked, choosing instead to expand the strike.

About 12,000 workers walked off the job on Sept. 15. Now about 45,000 are on strike, with some 7,000 more laid off due to related production disruptions. With some 52,000 out of 145,000 UAW workers out, the 2023 strike is also larger than the 2019 strike, which affected some 48,000 workers.

What it will take to end the strike is anyone’s guess. Barron’s originally predicted a 30-day strike, while Wall Street estimates put the number at 45 days. Those turned out conservative.

If a Ford deal happens it still could be mid-November before everything is wrapped up, at the earliest. That is still in time to have signing bonuses paid in time for the holiday season.

Wage increases in the range of 25% over four years, plus other benefit increases, have been on the table. Those could raise costs for the three by roughly $4 billion a year by the end of the contract. That works out to roughly 13% of the combined 2022 North American operating profit for GM, Ford, and Stellantis.

Would that be crippling? Only time will tell.

Costs go up at other auto makers too. UAW President Shawn Fain says his next job after wrapping up the 2023 negotiations will be to unionize the nonunion auto makers operating in the U.S.

Write to Al Root at [email protected]

Read the full article here

Leave a Reply