The term “Luddite” has been used as a pejorative term for centuries, as a way to suggest someone is fearful or ignorant of technology.

Brian Merchant wants that to end. He would like to see workers instead proudly wear the term today as they fight the kind of forces that turned English textile workers in the late 1700s and early 1800s into Luddites, who attacked factories and smashed machines that were destroying their jobs.

“It perpetually needs to be contested, this idea that a Luddite is somebody who’s dumb or backward looking. That sort of assumption benefits the people who make the most money making technology products,” the Los Angeles Times columnist and author told MarketWatch. “So it’s in the interests of a lot of people to keep the idea alive that to push back against [technology’s effects] is sort of automatically counter to progress or a bad idea or makes you dumb.”

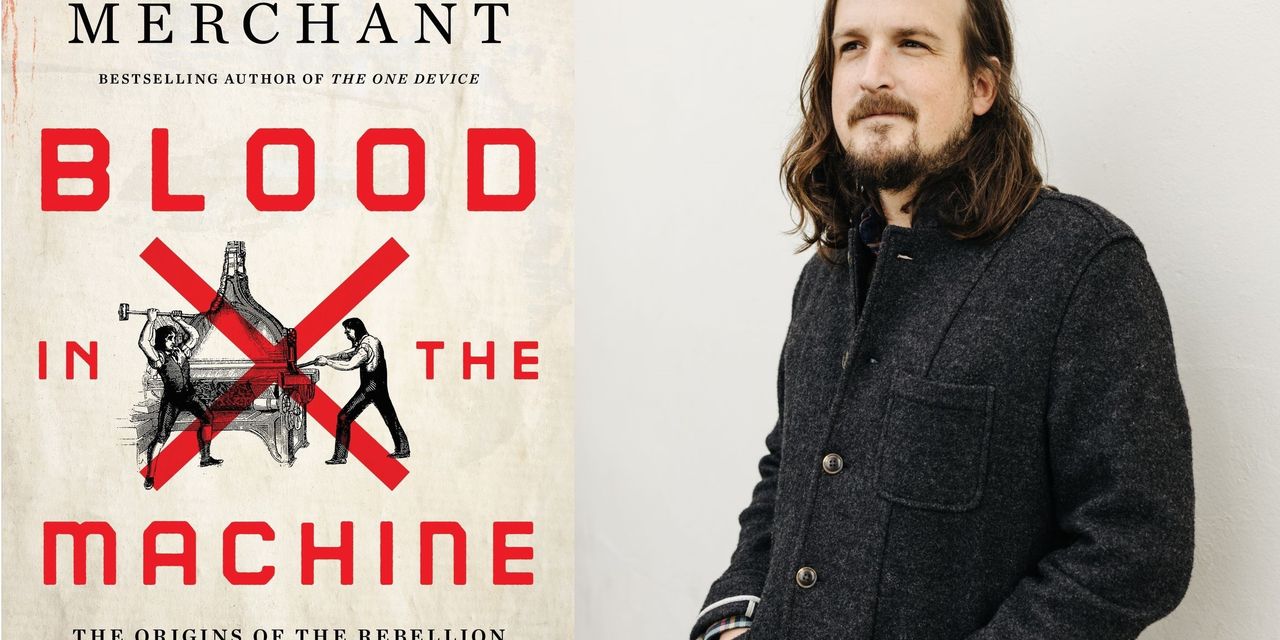

Merchant’s new book, “Blood in the Machine: The Origins of the Rebellion against Big Tech,” is available today, and it re-examines the history of the Luddites’ rebellion against the forces of the Industrial Revolution. Merchant also compares that story with current efforts to resist technological changes to workers lives from the effects of Big Tech and artificial intelligence.

MarketWatch recently spoke with Merchant about the book, how the two eras are similar and different, and what a worker rebellion in the AI era could look like. The interview has been edited for clarity and length.

MarketWatch: Your book describes the Luddites as workers who destroyed machinery that was being used by factory owners to automate their jobs in the hands of children and unskilled workers, and had the support of a majority of English people, eventually leading to changes in the law. Why is that not the story that has largely been told in the centuries since?

Merchant: The saying goes that the victors write the history books, and that’s very much true in the Luddites’ case. The [British government] kind of had an old-school propaganda campaign to paint the Luddites as backward from the very beginning, and they deployed the military to occupy the areas where the Luddites were active. So they also used a much more blunt tool to just crush the Luddites outright and to send this message that if you oppose technology, not only will we think you’re dumb and write that in royal proclamations, but we will also crush your movements physically by arming factory owners, by supplying military garrisons to protect factories and put them at the service of the entrepreneurs of the day. … Now the assumption is, if you’re a Luddite and you oppose technology, you’re doomed because technology inevitably advances and inevitably progresses and to go against it is foolish because the forces of technology are so powerful. And that’s not actually the full story.

The Luddites had a saying that showed up in the letters that they would write that they were ‘opposed to the machinery hurtful to commonality.’ and that’s really the key thing — it wasn’t about opposing technological development, full stop, it was about protesting the parts that were particularly exploitative, that were being used to degrade wages, to put them out of work, to allow the entrepreneurs to gain power and break the power of the workers.

MW: You write that what the Luddites faced is analogous to Big Tech and the current state of work, even though you were writing it before generative artificial intelligence arrived and threatened more jobs. Where do you see the strongest parallels, and where does generative AI fit in?

Merchant: You look at the past few decades, productivity has gone up and up and up, corporate profits and CEO pay have gone up and up and up, and yet worker pay has been stagnant. So it’s a great example of exactly the kind of thing that the Luddites were protesting, because a big part of that story is automation machinery, robotics and factories, software automation, things that are making workers more productive, but they’re just not seeing the benefits, and that’s what we stand to see more in this new AI era. If anything it’s going to serve the interests of the folks who either can afford the tools and make the decision to deploy them or companies selling AI outright.

I think that we’re in another moment that very much resembles the onset of the Industrial Revolution in the sense that we have a lot of people with access to tools that could be very disruptive if they can get the capital to put behind it, and there’s a lot of norms and standards and people with livelihoods that are suddenly feeling very vulnerable, especially creative workers, writers, artists, illustrators, stuff that can now kind of be done with generative AI. It doesn’t have to be done well, it doesn’t have to be done better than the human, it just has to be done well enough to meet the satisfaction of the boss or somebody who would be needing that service

MW: The Luddites were crushed by the government, but there were laws that sprung up from that period to protect workers. As the push for legislation to regulate AI begins, however, little of it seems to be focused on protecting workers in a similar fashion, especially in the wake of OpenAI’s ChatGPT.

Merchant: I think part of that is intentional. OpenAI and its ilk from the beginning have pushed this narrative that AI is all-powerful, so please regulate us so it’s developed safely. But they’ve moved the Overton window, or are trying to, so far down the line where they’re trying to consider existential crises — like the biggest threat is that AI is going to become Skynet, not that it’s going to be incredibly disruptive in the workplace. Meanwhile, they’re trying to do the very mundane thing of selling enterprise tech contracts because that’s where they’re going to make all their money. They’re up to a billion in revenues and that’s where it’s coming from.

On the one hand, it’s a huge oversight that we’re not looking at the labor implications here by and large, with the caveat that on the state level there are some interesting things being done. California has a bill put forward that would do things like help actors prevent AI replicas of them being used in contracts, giving them a little more power. That does kind of feel like nibbling around the edges a little bit, but it’s a positive development. But especially federally there’s a totally lackluster or even almost kind of lack entirely of attention given to the labor implications. And I would say that that’s, not surprising because that’s been the case for the last at least 10 or 20 years, having the keys handed to Silicon Valley and trusting them to build products and build platforms that are engines for the economy and are ultimately good for most people.

““You wouldn’t expect Americans to confront a technology, or even the use of an exploitative technology, head-on in this way and say, ‘no.’ And so that is kind of empowering a lot of people.” ”

MW: While I see the comparisons between the two periods, there are some stark differences, starting with the fact that about 80% of England was involved in the textile industry in some fashion in the Luddites’ era, but now we have a wide variety of industries at different maturity stages — Amazon

AMZN,

has seen some early organizing efforts that you write about, Hollywood is heavily unionized and just went on strike to fight AI, while industries like gig work are not organized at all. How do workers find common ground to work together across industries?

Merchant: It’s a real consideration and it’s a hard question. One thing that has happened to our economy at large over the last couple of decades now as inequality has widened, as housing prices have gone up, as conditions have sort of worsened for the middle class, I think more people are starting to feel what old-school folks would call class consciousness. There’s a lot of Millennials who are now sort of coming to grips with the fact that, as things stand, they are never going to be able to afford a home despite playing by the rules. There’s a lot of industries that are very precarious and even if you have a good job, there’s a sense that it could fall away. So I think at a base level, there’s a familiarity in a way that, maybe 20 or 30 years ago, wasn’t the case — the overworked UPS

UPS,

driver can relate to the underpaid journalist, who can relate to the freelance artist whose work is being gobbled up by Midjourney ,who can relate to the coder who’s gotten fired from his second Silicon Valley company within the space of 18 months.

I think it’s really interesting that we’re seeing such stark protests against AI or the use of AI in the workplace from WGA to SAG, those artists. That feels, at least within my lifetime, like a new thing — you wouldn’t expect Americans to confront a technology, or even the use of an exploitative technology, head-on in this way and say, ‘no.’ And so that is kind of empowering a lot of people. And there is overlap between a lot of these issues. One of the big things in the auto workers strike is that it requires less labor to make EVs, so that’s a point of contention. How do you deal with that? How do you deal with what is basically automation on the factory line? So there is there is a lot of overlap but I think it’s easier for people to kind of see solidarity with each other. At the same time, just look at Silicon Valley. These tech companies are beyond rich, beyond powerful. The people that run them or that founded them are among the richest in human history and some of them have proven themselves to be controversial at best and bad actors at worst and have seen their public stock go way down. So it’s all kind of a recipe for some more united protest or more united organizing than we’ve seen in a while.

MW: What does that united protest look like, though? The equivalent to what the Luddites did in their day would be overrunning data centers or something similar — physically attacking the tech at the center of the issue. I don’t think you’re advocating for that, but if workers can organize across industries, what does the collective action look like?

Merchant: The important difference is that the Luddites were barred legally from organizing — it was illegal to form a collective bargaining unit, basically, you could be arrested for that. It was also in a time before democracy, so there is no democracy. So I don’t think that we will see the mass adoption of some sort of sabotage tactics in quite the same way so long as we do have access to those tools, and that’s why it’s more of a spiritual adoption of the tactic like when you’re rejecting a technology in a labor contract.

To your larger question — where do you harness all of this and target it — the best answer we have right now is folks continuing to organize. I mean organized labor is more popular now, for a reason, than it has been in decades. It’s touching Starbucks

SBUX,

It’s touching UPS, its touching the tech companies, its touching Amazon, its touching everywhere. … We’re at a moment where people are supportive of organized labor, are really excited and invigorated by this moment. The UPS drivers won a historic contract and even though the Amazon labor union has had a bunch of defeats, I think there’s still a lot of optimism that things will trend toward more victories in the future.

Right now, there’s a lot of ways to channel a modern Luddite energy into productive projects. My fear would be is if the bottom drops out of the economy, if we see a crash. Right now, we have a pretty tight labor market, we have pretty solid employment even though people justifiably want to make more money and housing costs are too high. But if there was an X Factor injected into the mix, then I think we’re in a place where trouble could find us pretty quickly.

For more: Unions’ push at Amazon, Apple and Starbucks could be ‘most significant moment in the American labor movement’ in decades

Read the full article here

Leave a Reply