Joe Genovese was hired by Ford Motor at the tier-two level, as workers refer to it, 11 years ago. In a year, he’ll finally make top pay, he told a United Auto Workers rally earlier this month.

Tier-two workers in the automobile industry can receive less than half as much in hourly wages as top-tier workers, depending on the automaker and the contract. Their benefits are also less generous — and, like in Genovese’s case, it takes them many more years to reach the top hourly wages than those hired before 2007, when the Big Three automakers introduced the current tiering system after their financial troubles.

Because of this, Genovese said, he has seen many friends and family members who were also tier-two employees transfer to other plants during his time at the company, as they sought to increase their pay however they could.

“With tiers, there is no union,” he told the crowd of hundreds of union workers near Detroit during the Aug. 20 rally, which was livestreamed. “With tiers, there’s a division. It’s time to close that division.”

The union has been dissatisfied with its negotiations with the Big Three automakers, and announced Friday that 97% of members had voted to authorize a strike if no agreement is reached. Contracts are set to expire Sept. 14.

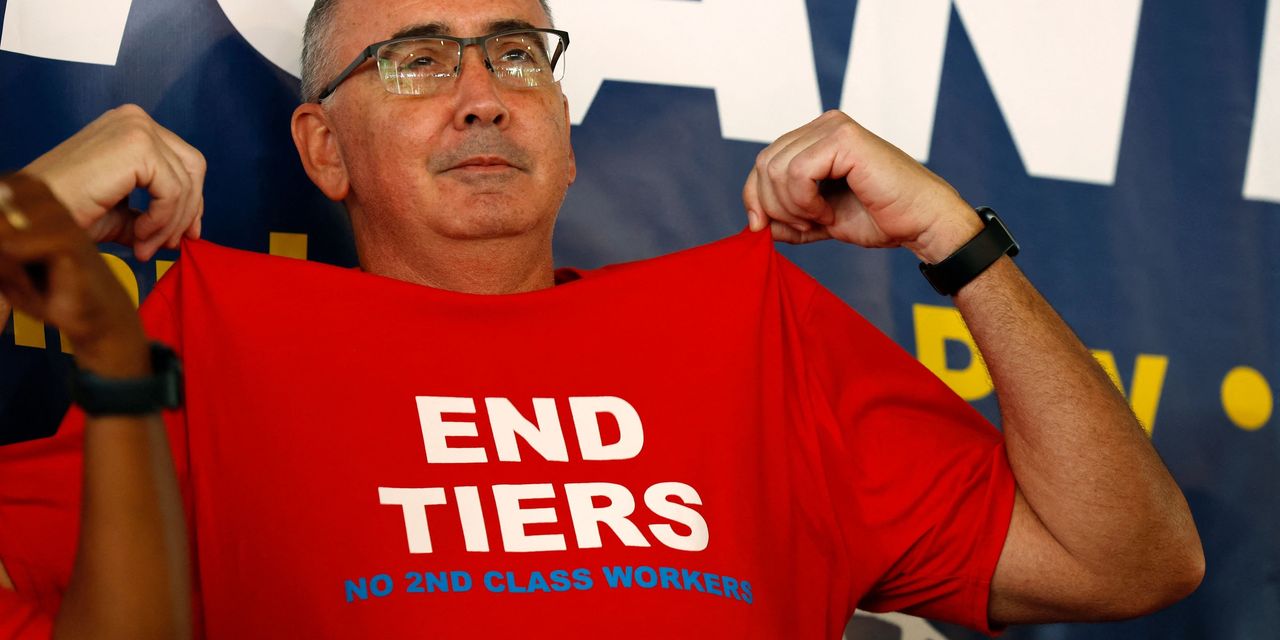

One of the union’s priorities is ending the automakers’ tiered workforce. Shawn Fain, the UAW’s president, wore an “End Tiers” T-shirt at the recent rally.

‘A sore point from Day 1’

Tiering, an increasingly common practice that labor experts say started in the U.S. in the 1980s as employers pushed for concessions from their employees, is when companies bring in new employees for lower pay and fewer or worse benefits — sometimes on a supposedly temporary basis that can stretch on for years — than workers hired earlier who are doing the same work.

In the U.S. automobile industry, workers hired in 2007 and onward don’t have pensions or healthcare when they retire. In addition, as automakers make the transition to electric vehicles, so-called new types of work are being performed that may not be covered by UAW contracts, such as by workers at some battery plants that have not been unionized. That worries unions and labor observers alike.

“‘Across the board, the rank-and-file hated [tiering]. … They viewed it as discriminatory that people were doing same job and getting paid substantially less, and that [some workers were] treated as second-class citizens.’”

Nelson Lichtenstein, a professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara who has written books about the history of labor, said that in the ’80s, tiered workforces could be found not just in the automobile industry but in airlines and trucking, too. Now, many “employers are constantly creating new tiers. It fits in with the fissuring of the workplace,” he said in an interview before the results of the strike-authorization vote were released.

U.S. automakers over the years have justified tiering as a way to stay competitive because of globalization, Lichtenstein said. “Whether the automakers are doing well [financially] or not, they’ll say the competition, like Toyota, will eat our cake.”

But “across the board, the rank-and-file hated [tiering],” said Marick Masters, a business professor at Wayne State University in Detroit. “It was a sore point from Day 1. They viewed it as discriminatory that people were doing same job and getting paid substantially less, and that [some workers were] treated as second-class citizens.”

Other auto workers tell stories that are similar to Genovese’s.

Quortez Danforth, a UAW Local 1264 member in Sterling Heights, Mich., who has been a temporary part-time worker at Stellantis for five years, also spoke at the rally. He said he had “missed out on rolling over” to a full-time job in 2020, when he had to have open-heart surgery. Since then, he said, he has lost out on three years of bonuses and profit sharing, to which full-time permanent workers are entitled.

“I’m hoping this [union] fight will help,” Danforth said.

Tony Totty, the president of UAW Local 14 in Toledo, Ohio, and a General Motors employee, told MarketWatch ahead of the vote results that the union and workers have made concessions for years as U.S. automakers went through tough financial times, including bankruptcies and bailouts.

“If we didn’t make those concessions, these [companies], managers and CEOs wouldn’t be making what they make,” Totty said. “Now they’re so profitable, but we still have these provisions from the days of bankruptcy.”

GM

GM,

and Ford

F,

posted $2.6 billion and $1.9 billion in profit in the second quarter, while Stellantis

STLA,

the Dutch multinational automaker that is the parent company of the U.S. automaker formerly known as Chrysler, reported $12.1 billion profit in the first half of 2023.

A GM spokesperson would not comment on tiering but issued the following statement: “We’ve been working hard with the UAW every day to ensure we get this agreement right for all our stakeholders.” A spokesperson for Stellantis referred MarketWatch to the company’s website about the negotiations with the union. Ford did not respond to a request for comment.

Totty, who was hired by GM in 1997, said it took him three years to reach top rate, or the highest wages possible. “Now it’s an eight-year progression. Now there’s other things that will never get them to 100% in the contract,” he said. “I have a pension; they don’t. That pension allows me to get retiree healthcare. They don’t get that.”

As for the issue of automakers striking partnerships with other companies to make batteries for EVs and using nonunion labor, battery-plant workers are starting out at a lower hourly rate of $16 to $20 an hour, Totty said. He expressed concern about what will happen to other workers once the transition to EVs is complete.

“GM has had partnerships before, like with NUMMI [a joint venture between GM and Toyota that had an automobile plant in California], done with all UAW workers,” Totty added.

A game of whack-a-mole

Jody Calemine, a senior fellow and director of labor and employment policy at the Century Foundation, a progressive think tank, likened tiering to a game of whack-a-mole. Tiering exists everywhere, he said, including at grocery stores, in healthcare and in the public sector. It exists in delivery, including at the U.S. Postal Service.

Teamsters at UPS

UPS,

were able to eliminate one tier — a second tier of lower-paid drivers — in the contract the company’s employees approved last week. But a part-time UPS warehouse worker, Noah Jorstad of Fargo, N.D., told MarketWatch that under the new contract, there remains a difference between what current part-timers will make by 2028 ($25 or $26 an hour) and what new hires’ hourly wages will be by that time ($23 an hour).

“It’s going to be an issue for the next contract,” he said. “It’s like kicking the [can] down the road.”

See: It’s ‘crunch time’ for unionized auto workers, but this is not UPS

Saving difficult issues for later has been a recurring theme in labor negotiations since companies introduced tiering in the ’80s, Calemine said. For the companies, it was “a very clever tactic,” he said. “It ended up being the cheapest concession a union could make in the moment. Though unions resisted it, no current member was losing anything.”

“‘We need to be the working class again, instead of the working poor.’”

Perhaps nowhere are the effects of tiering more obvious than within the same family.

Sarah Schambers, a fourth-generation Ford worker in Michigan and single mother of two children, said in a video recently released by the UAW that it took her six years to go from a temp job to a permanent position that paid $16.66 an hour. And it took her a total of 15 years to reach the top wage of $32 an hour at the company, she said — after having to move plants four times, from Michigan to Kentucky and back.

By contrast, it took her mother just three years to get to top pay, she added.

Even when she was working 40 hours a week for Ford, Schambers said, she would make deliveries for the grocery-delivery app Instacart “so I could make sure that my bills were paid and that my kids had everything they need.”

“I don’t think that’s freedom,” she said. “We need to be the working class again, instead of the working poor.”

Related: Actors, writers, hotel housekeepers and grad-student workers are all striking for the same reason

Read the full article here

Leave a Reply