Attorneys gave their closing arguments Wednesday to the jurors who will decide Sam Bankman-Fried’s fate, offering two diametrically different versions of the collapse of his crypto empire.

US Assistant Attorney Nicholas Roos presented the government’s view that Bankman-Fried is guilty of stealing money and engaging his business partners in a cover-up.

Roos described the scheme as “a pyramid of deceit, built by the defendant on a foundation of lies and false promises — all to get money.”

Eventually, Roos continued, “it collapsed, leaving countless victims in its wake.”

Bankman-Fried’s lead defense attorney, Mark Cohen, pushed back on what he described as the government’s “wrong and unfair” portrayal of his client as a greedy “movie villain” who set out to defraud people from the start.

The reality, Cohen said, is far less cinematic. Ultimately, he argued, the government has failed to meet its burden of proof that Bankman-Fried masterminded a yearslong conspiracy to defraud customers, investors and the public.

The case centers on the collapse of FTX, the crypto exchange founded by Bankman-Fried, that spiraled into bankruptcy a year ago, leaving hundreds of thousands of customers locked out of their accounts and unable to move their money. The fraud, according to the government, was happening behind the scenes, while Bankman-Fried’s other firm, Alameda Research, was secretly siphoning money from customer deposits.

Roos told jurors that the core issue in dispute in the case was whether Bankman-Fried knew that taking the money was wrong, and not simply an honest mistake carried out by an absentminded startup founder.

“The answer is clear: He took the money, he knew it was wrong, he did it anyway,” Roos said. “Because he thought he was smarter… he thought he could talk his way out of it.”

The prosecutor said that when Bankman-Fried took the stand, testifying for three days before the jury, “he told you a story, and he lied to you.”

Bankman-Fried “came up with a tale that was conveniently put together to exclude himself from the fraud.”

Roos noted that Bankman-Fried was confident and had a “perfect memory” when questioned by his own attorney. But under cross-examination, “suddenly… he couldn’t remember a single detail about his company. It was uncomfortable to hear.”

Taking aim at Bankman-Fried’s defense that his companies had “messy accounting,” Roos said: “I mean, gimme a break — that was a lie.”

Ultimately, Bankman-Fried thought it was OK, and claims he wasn’t aware of many of the actions in question. But “not a single other witness” has said the same. The government’s witnesses, which included three senior executives in the defendant’s inner circle, saw the commingling of funds as “a bright red line.”

Over several hours, Roos sought to illustrate how Bankman-Fried was fraudulently duplicitous for years as he built out his crypto empire.

Repeatedly, Bankman-Fried told reporters, customers, investors and lawmakers that customer deposits were safe. While saying publicly that FTX was “wholly separate” from Alameda and a “neutral piece of market infrastructure,” Roos said, Bankman-Fried compiled a spreadsheet that showed Alameda’s $65 billion line of credit — one of several secret, special privileges afforded to Alameda as a customer of FTX.

The “public lies” show his criminal intent, Roos said.

As Roos spoke to the jury, Bankman-Fried kept his eyes trained on his laptop, occasionally typing and scrolling.

His parents, Joseph Bankman and Barbara Fried, greeted their son briefly in the morning before the trial began, but were absent during most of the government’s closing argument.

Cohen began his closing statement around 3 pm, directly pushing back on the government’s narrative.

“Time and again, the government has sought to turn Sam into some sort of villain, some sort of monster,” Cohen said. “It’s both wrong and unfair.”

“They wrote him into a movie villain” to make jurors overlook the facts, he said.

Cohen even took aim at Roos’ cinematic pointing to the defendant (“that man” Roos called him) — a move Cohen said was done “for the effect.”

In perpetuating the movie-villain narrative, the government fixated on Bankman-Fried’s hair, his clothes, testimony about his sex life, photos of him sleeping on a private jet or posing awkwardly with celebrities.

“We’ll agree that there was a time when Sam was probably the worst-dressed CEO of all time,” Cohen quipped. “But that’s not a crime.”

The government’s case is based on a “false premise” that FTX and Alameda were fraudulent from the start, Cohen told jurors. To hear the government tell it, four people got together and set out to start a criminal enterprise, he said. But the evidence shows those people were friends who believed in the business they were building — companies that “were legit, valid, innovative businesses.”

“In the real world — unlike the movie world — things can get messy,” Cohen said. People “make mistakes that later on they wish they could have fixed.”

Cohen underscored Bankman-Fried’s own admission that FTX lacked “a significantly built-out risk management system,” and didn’t have a chief risk officer.

“Poor risk management is not a crime,” Cohen said.

If Bankman-Fried were such a criminal mastermind, Cohen asked the jurors, “why would he go before Congress and subject himself to public questioning? Answer: He wouldn’t.”

Over three hours, Cohen sought to undermine the government’s key witnesses: Caroline Ellison, Gary Wang and Nishad Singh, who were all close friends and executives in Bankman-Fried’s inner circle. They also rode the rise of FTX and Alameda to create personal fortunes.

“These were extremely wealthy people” who could have, at any time between 2020 and 2022, when the alleged crimes were happening, taken their money and run. They could have cashed out, notified authorities, hired lawyers. But none of them did, Cohen said. Because in the moment, “they don’t think they’re doing anything wrong.”

But once the collapse of FTX began in November 2022, “they did what they had to do,” he said.

Cohen told jurors that those witnesses “won’t get their deal” — a lighter sentence in exchange for their testimony — if they say “Sam was our friend” or that he was doing his best to save the company.

“You should consider their testimony overall very carefully,” Cohen said.

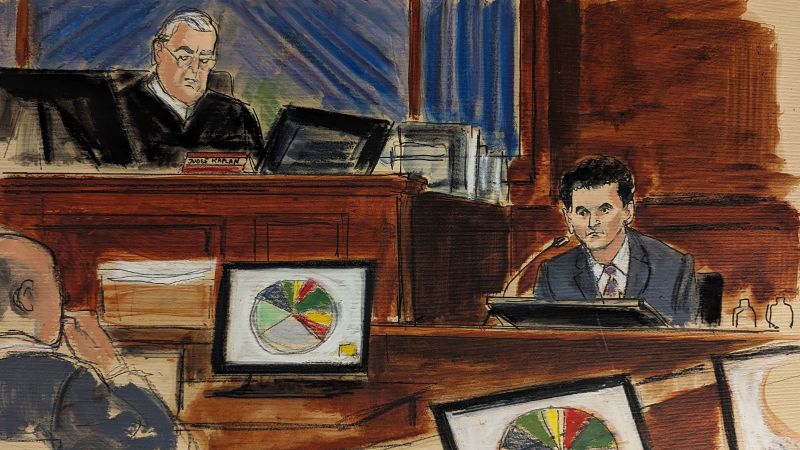

Closing arguments ran well past the usual 4:30 pm adjournment, as Judge Lewis Kaplan seemed eager to give the case to the jury Thursday morning.

As Cohen wrapped up his speech around 6 pm, his voice sounding hoarse, he asked jurors to consider the defense’s view as they deliberate.

“Business decisions made in good faith are not grounds to convict,” he said. “There was bad judgement. That does not constitute a crime.”

Bankman-Fried’s mother, Barbara Fried, was visibly shaking while listening to lead defense attorney Mark Cohen deliver his closing arguments.

His parents entered the room only when Cohen began closing arguments, opting to leave the courtroom when Roos detailed the alleged crimes for over three hours.

They entered the courtroom in the morning said hi to their son and embraced him quickly, leaving before the government began.

During defense closings, Fried seated in the second row of the galley, intensely watched her son.

She was visibly shaking and rocking her body back and forth in her seat at times, her hands either clasped together, fingers intertwined, or pushing her sleeves up her wrist, and crossing her arms. Her mouth and jaw quivered at many moments during Cohens delivery.

Bankman-Fried’s parents approached him during a break after lunch, his father giving him a smile, and a thumbs up .

At the end of the day, Bankman-Fried appeared to be crying as Cohen delivered his final thoughts.

At the end of the day after closings, his parents embraced defense attorneys and said “thank you…thank you.”

Read the full article here

Leave a Reply