Even before the House reversed course last-minute to attempt to head off a shutdown, the endgame was relatively clear. A shutdown would likely end in a modest Washington, D.C., compromise to avoid the biggest disputes, accompanied by drama over who gets to do the impossible job of speaker of the House.

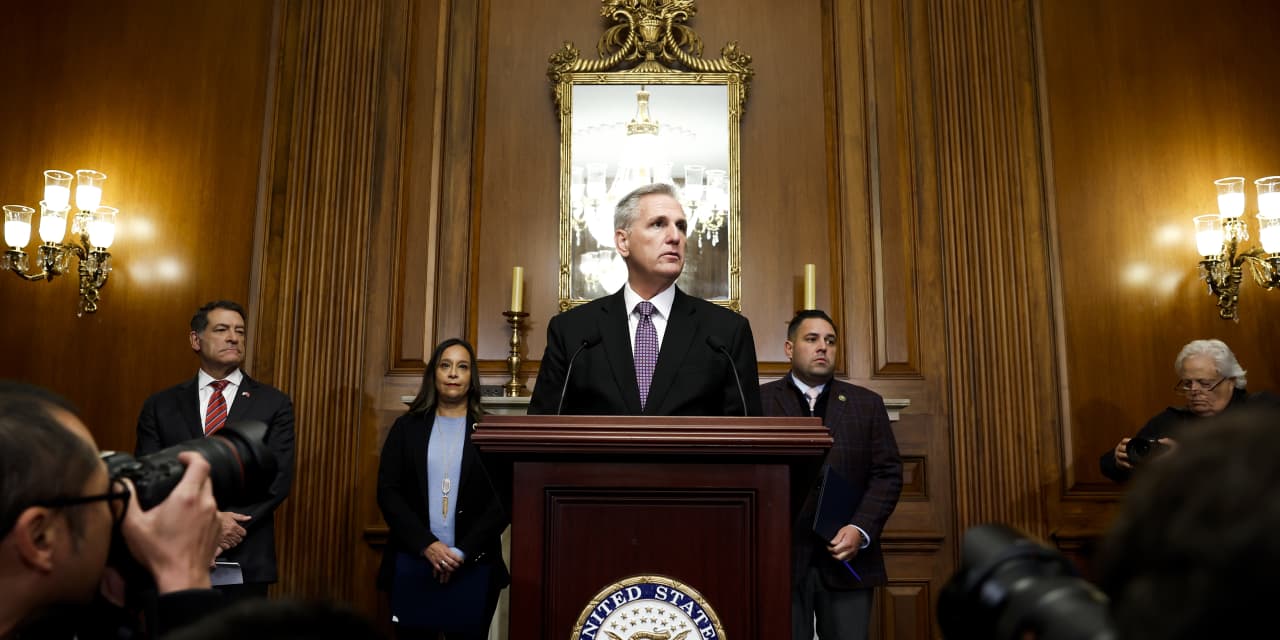

Congress cut to the chase on Saturday and passed a bill that did just that, keeping the government open for 45 more days, increasing disaster spending, and avoiding the issue of aid to Ukraine, for now. That would put the question of a shutdown to bed for now, though it won’t necessarily settle questions over House Speaker Kevin McCarthy’s leadership. In a press conference after the House vote, McCarthy addressed members of his party who he said had resisted measures to keep the government open. “I don’t want be a part of that team,” he said.

Investors who’ve been tuning the story out so far are likely feeling good. A Washington shutdown isn’t market-moving event, although it would weigh on people like the military service-members and civilian federal employees who deserve to get paid on time.

But looking at a shutdown as a discrete political event misses the point. The more consequential forces—the ones Moody’s warned about recently when it said a shutdown might make it the third of the big ratings firms to downgrade U.S. debt—didn’t arise with the end of the fiscal year, and haven’t gone away even with a tentative deal. That’s what investors need to pay attention to.

An era of political polarization is producing tight margins in the U.S. Congress. A couple of politicians can stymie the rest of the government’s plans. And that’s not only Republicans. Many Democrats were frustrated with Sens. Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema during legislative negotiations early in President Biden’s term.

One of the functions of Congress in a divided government is to act as a check on the executive branch, so, with the deficit likely landing at $2 trillion this year, in a sense this Congress is upholding its mission. But with a tiny 221-212 majority, House Republicans have had difficulty coming up with a unified negotiating position other than saying “no” to spending.

That’s a key difference between this government shutdown threat and the possibility earlier this year of a debt-ceiling breach. In the earlier fight, House Republicans surprised the Biden administration by passing one bill expressing their collective views well in advance of the X-date. This time, the effort to come together on a collective plan still hasn’t coalesced into a package House Republicans support. The stopgap measure passed because Democrats also supported it, and Republicans still haven’t passed all the appropriations measures that would fully set out their budget policies.

Shutdowns cause political pain, and that’s ultimately what drives agreement on how to end them, said Eric Cantor, a Republican who served as House majority leader during the 2013 shutdown, which also featured a debt-limit fight. He’s now vice chairman and managing director at the investment bank Moelis. “That’s always the central fault in any shutdown strategy. There’s never a clearly conceived notion of how you exit,” he said.

Once a shutdown starts, it’s anyone’s guess how long it will take to find an exit strategy. The last shutdown lasted more than a month.

A major question now is whether there will be a challenge to House Speaker Kevin McCarthy’s leadership. One of the commitments that allowed him to become speaker in January also allows any of his fellow House Republicans to call a vote on his leadership. He may survive a challenge, and Cantor points out McCarthy was written off too early in the debt-ceiling fight. But it’s likely that the aftermath of that fight will leave angry holdovers who supported the loser.

That, of course, would leave the House simmering with frustration, making every future vote harder. But with the debt ceiling resolved until after 2024’s election, the stakes might seem lower from here. If only that were true. “The more you normalize dysfunction, the more dysfunction will be the normal,” said Casey Burgat, the director of the legislative affairs program at George Washington University’s Graduate School of Political Management.

Take Social Security. Double-digit benefit cuts will be necessary if a fix for persistent shortfalls in the trust fund isn’t found in the next 10 years. A golden opportunity could be approaching, in either a second term for Donald Trump or Joe Biden, when legacy-defining compromises tend to be on the table. “Social Security has only ever been addressed in divided government,” Louisiana Sen. Bill Cassidy told Barron’s recently.

But that’s unlikely in a government as divided as this one. That’s why Moody’s warned it may downgrade U.S. debt in the event of a shutdown. Planning for anything other than the short term “appears extremely difficult in the current highly polarized political environment,” the ratings firm wrote on Monday.

Wall Street has a habit of looking at government divisions as positive for markets, since it means the policy baseline won’t change. But that thinking is out of date, explained Brian Bartlett, a veteran of Republican politics who is now a partner with D.C. communications firm Kekst CNC. The parties have adapted to their narrow margins by getting better at passing legislation without any votes from the other side, like the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act or the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act. The narrow national political margins mean that we’re likely to oscillate between short periods of temporary total control by each party. Policy will rapidly push the economy in one direction and then another, constantly ramping up the uncertainty.

“It used to be that the pendulum would swing back and forth, but the magnitude of the swings weren’t as large. Now it’s going to be much bigger swings that happen,” Bartlett said.

The great strength of the U.S. system is that a robust private sector often dampens those political swings. There’s every reason to believe that will be the case this time around, too—the shutdown drama of 2023 will be yet another chapter in a story of a dysfunctional Washington that markets can largely shrug off.

It’s fine to think that way. Just don’t assume you know how the story ends.

Write to Matt Peterson at [email protected]

Read the full article here

Leave a Reply